Winter Field Day, Summer Field Day, "Summits On The Air" with W7MRC, Amateur Radio, Rhodesian Ridgebacks, Field Craft, Living in Montana, Old 4 Wheel Drives, Old Tube Radios, Hiking and "Just Getting Out There"

Sunday, April 28, 2019

How Augmented Reality Will Create a World of On-Demand Experts

How Augmented Reality Will Create a World of On-Demand Experts: Anyone will be able to access the right information to perform the right set of skills, whenever and wherever they need it.

73 EASTING: THE LAST GREAT TANK BATTLE OF THE 20TH CENTURY By Neil Fotre

While many movies have been made about battles in the current Global War on Terror and the controversial Vietnam War, few offer a glimpse into the Persian Gulf War and its lesser-known engagements. You’d have to dig even deeper for significant battles involving armored tanks. The best bet for a look at a tank engagement in Operation Desert Storm is the 1996 Denzel Washington movie “Courage Under Fire.” However, the Battle of 73 Easting was an impressive feat and is considered one of the great tank battles of the 20th century.

Immortalized in Mike Guardia’s book “The Fires of Babylon: Eagle Troop and the Battle of 73 Easting” and the documentary “The Last Great Tank Battle of the 20th Century,” the Battle of 73 Easting was fought on Feb. 26, 1991, during the Persian Gulf War, also known as Operation Desert Storm.

The Battle of 73 Easting - The Most Intense Tank Battle In History on Youtube

President George H.W. Bush was banking on the six-week offensive of Operation Desert Storm to solidify his re-election. American media was able to shed a patriotic spotlight on what was known as the American military’s “shock and awe” tactic to defeat Saddam Hussein’s army. Amidst now-famous world news coverage of airstrikes and bunker-busting missiles, the Iraqi Army harbored a massive armored vehicle force that rivaled many other countries in the world. At the peak of its military might, the Iraqi Army touted the fourth-largest army on the planet. It had the ability to raise 2 million troops if reserve units were called to arms. But that would soon change.

The majority of the war was filled with airstrikes and a sweeping offensive by 20,000 American troops along with a coalition of foreign militaries from several other countries. The Battle of 73 Easting was fought toward the end of the offensive, after Iraq’s military had been greatly softened by the air campaign. Massive troop desertions and surrenders were a common sight across the Iraqi landscape. The iconic photos of Iraq’s swift defeat were plastered all over the news as the fleeing army set oil fields ablaze to cover their retreat and exposed flanks.

The Iraqi Republican Guard and its Tawakalna Division were all that remained of the Iraqi military in the final days of the U.S. offensive. They had taken defensive positions near a north-south coordinate line, commonly referred to as an “easting.” These coordinate lines are measured in kilometers and can be read via a global positioning satellite (GPS). This area was referred to by a grid coordinate line because the desert was completely void of any geographic landmarks or population center.

The major U.S. unit that was involved in the battle was the 2nd Armored Cavalry Regiment (2nd ACR). The regiment was comprised of three ground squadrons, an aviation squadron, and a support squadron. Within each squadron were three cavalry troops, a tank company, a self-propelled howitzer battery, and a headquarters troop. Each troop was comprised of 120 soldiers, 12 M3 Bradley fighting vehicles, and nine M1A1 Abrams main battle tanks. The regiment totaled approximately 4,500 troops.

The Iraqi force greatly outnumbered the American units. Each of the Iraqi units possessed approximately 3,000 soldiers and had significantly more armored vehicles. The Iraqi units were also set in a defensive posture, which offers a significant advantage during battle.

The mission of 2nd ACR was to motor eastward. The regiment’s advance was led by its scouts in M3A1 Bradleys. Located behind the Bradleys were mighty M1A1 Abrams tanks that provided rear protection while the scouts helped to identify enemy positions. While advancing, the regiment was to clear out any enemy security forces and neutralize the Republican Guard.

The American units had a superior technological advantage. Within the confines of the crewmembers space in the vehicles, the gunners possessed an advanced thermal targeting acquisition system.

The majority of the Iraq armored vehicles were old Soviet-era type vehicles. The primary tanks used by the Iraqis were the model T-55, T-62, and T-72. The main battle troop carrier was the BMP-1. Each of these vehicles has a manual form of targeting, which is far slower to operate than that of the Abrams and the Bradleys. Also, the optics on the American vehicles allowed for “dark” engagements, meaning that the vehicles could fight at night and didn’t necessarily need a clear line of sight to engage.

The cannons on the Abrams carried a higher caliber round, far superior to the Iraqi tanks. Desert Storm was the first extensive use of the depleted uranium high explosive and armor-piercing rounds. The Soviet-era vehicles could not withstand the impact of these devastating charges. The American vehicles, on the other hand, possess “sloped” or “angled” armor that stood a much higher chance of deflecting enemy projectiles. Bradleys, despite being equipped with a much smaller 25mm “Bushmaster” cannon, were outfitted with tube-launched, optically tracked, wire-guided missiles (TOWs). This missile is easy to operate and highly effective at destroying enemy armor.

The Battle of 73 Easting did not last long. The mechanized force was brought to its knees with minimal American casualties. Estimates vary on the exact number of casualties due to certain incidents of friendly fire, but the Iraqi damage is estimated at almost 1,000 soldiers killed in action and more than 1,000 taken prisoner. These staggering figures came at a cost of a mere 12 Americans killed in action. Essentially, the fourth-largest Army in the world was neutralized in less than 96 hours through the use of well-trained tactics and superior technology.

For the first time since tank battles of World War II, the Battle of 73 Easting saw two modern armies slugging it out in fully mechanized warfare. The stunning performance of American troops in the battle is taught as doctrine to this day.

Expedition 65 by Colin Evans

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Overland Journal, Gear Guide 2018. Photography by Alfonse Palaima, Scott Brady, and Colin Evans

Expedition 65 was not a tour; it did not even have a leader. While some might view that as a recipe for ending friendships, it played into a grand experiment and ultimately a transformative experience. The concept was born from a rushed trip to Bolivia and became a very rushed trip all the way to Ushuaia. Here is the hard reality of travel: there is never enough time—ever. That is how life works. However, there is more that can be gained from adventure, like the rapport established with those we ride with, and the changes to our notions of the world, shifted by the perceptions that form by actually being there. This is a story of those insights and those friends, with a bit of adventure thrown in for good measure.

#EXPEDITION65

We had a hashtag; now we needed a plan. We were a dozen friends bringing their different skills, life experiences, and personalities to execute a ride. It was decided to ship the bikes to Cartagena, Colombia, ride to Ushuaia, Argentina, and then ship everything back home from Punta Arenas, Chile. From the Caribbean to the Antarctic, 10 degrees north of the equator to 55 degrees south. Over 10,000 miles through six countries, with 13 border crossings. The scale was huge and overwhelming, but it turned out to be the ordinary encounters that made the most impact.

A NEW FRIEND

I came to South America to meet South Americans. We arrived in Huamachuco in the Northern Highlands of Peru looking for lunch, a place to rest, and time to plan our next steps. We found a restaurant on the town plaza and, across the street, a couple of old gentlemen watched the world go by as they probably did most days.

We were soon answering questions from onlookers around our bikes. Who were we, where were we from, where were we going? But these gentlemen remained reserved and distant, their old-fashioned manners making it impolite to intrude. So I went over and sat on their wall and chatted and found out that Fernando and Cesar were farm workers who had retired long ago; they had the same questions as everyone else but were too dignified to ask. Fernando took a photo of me with his ancient cell phone and proudly welcomed me to his town surrounded by hard farming and toxic mining. He was way too old for a photo on the bike but wanted a picture with me and asked for a copy. I asked for his address, but he pointed to Foto Rodriguez on the corner of the plaza. A few minutes later, with the card from my camera, Señor Rodriguez produced two 4×6 glossy photos for which he adamantly refused payment. Fernando took the photo with dignity but without a smile. In the street, he unexpectedly hugged me and went on his way. We had both made each other’s day very special.

DIFFERENT JOURNEYS

Adventure motorcycling brings together people of significantly different political and personal beliefs around a common passion. We had one idea but many different expectations and motivations: escape, adventure, discovery. The scariest roads or intimate personal encounters. If another member of the group wrote this account, it would be an entirely different story. For me, it was a journey to experience six countries, explore a thousand years of history, and learn something about myself. It wasn’t just about the terrifying roads, spectacular scenery, new food, smells, and people—but about new perspectives, camaraderie, and challenges that ultimately revealed how lucky we are to have been born where and when we were. At the start we all half knew each other, but in months of shared experiences you inevitably reveal more of yourself, and at the end, we were brothers. Nobody was in charge, but everybody took responsibility.

HOW TO THROW A PARTY

Angasmarca is an unremarkable town in the Central Highlands of Peru. There are no pre-Incan ruins, no Spanish colonial buildings, no handicrafts markets. Just a small concrete plaza separated from any passing tourists by difficult dirt roads over almost impenetrable mountains.

But we rode into Angasmarca on the town’s birthday, the annual celebration of its founding. Our path was blocked on every street. As we stopped to see what was happening, it seemed that every school, church, civic organization, and indigenous group was parading for the rest of the town—marching, singing, dancing, and being applauded from a sea of leather-like faces and enormous straw hats.

Very soon, the curious kids and more adventurous adults came over to chat with us, and a conversation started about why we were in their town this lovely Sunday afternoon. Then came the photographs, well wishes, welcomes, giggles, and the general breaking down of barriers that happens every time we stay long enough.

As we were getting ready to leave, a couple of groups of people appeared dressed in their traditional colors carrying palm fronds, each led by a man in a knitted mask with holes for eyes and mouth. Suddenly we were surrounded and pulled in by one of the masked leaders with a rope in the form of a snake. When we tried to extract ourselves, we learned that it was considered rude to leave before the song was finished, but we had to go. This was no place to be riding at night. Finally, a police officer with an ancient revolver helped steer away the people so we could ride and not hurt anyone. Angasmarca, we will be back on your next birthday.

THE MOST DANGEROUS ROAD

Riding in the Andes is breathtaking, electrifying, and completely terrifying. Leaving Pallasca, we dropped 7,000 feet into the Rio Tablachaca Valley, on roads where there was zero room for error—one slip and there was the abyss.

This road was once paved, but now large sections have slipped away after landslides or earthquakes and have been crudely patched. Even on sections that are still intact and paved, trucks and buses have ripped every hairpin bend into potholes, and huge sections have a mound of pebbles and scree in the center of the road. This is no problem for trucks, but a nightmare for motorbikes. You cannot look at the road and the scenery at the same time here, even for a second.

LAND OF CONTRASTS

Traveling in South America is a constant battle between the outstanding natural beauty and the choking poverty and pollution of the towns and cities. Municipalities are overrun with farm animals, construction and detours everywhere, roads jam-packed with ubiquitous passenger vans shuttling people in all directions, and buses and trucks with unmaintained diesel engines spewing carcinogens in indiscriminate black clouds.

La Paz, Bolivia, is a perfect example. There is no city in the world more visually stunning than La Paz; it sits in a canyon that has protected it from Altiplano winds and the worst of the high altitude weather for centuries—the views of the city are amazing. It was originally a small mining town before the Spanish showed up and took over. Today, it is spilling further and further down the canyon with unplanned building continuing on every slope.

But the combined population of La Paz and neighboring El Alto is over 2.3 million people, and they are crammed into a place with no level ground, money, or ability to create effective public transportation. When we arrived in El Alto, the main road to La Paz was dug up for over 5 kilometers, and we resorted to riding our big BMW bikes along the roadworks at dusk, trying not to strike the puzzled onlookers who scurried out of the way.

It seems that the citizens of El Alto are fed up with the roadworks too. Every road was blocked with peaceful demonstrations by local lady organizers in bowler hats, carrying children and provisions in their shawls, campaigning against the mayor. Less money on roads and more money on education was the basic message.

BEAUTY VERSUS REALITY

Of the countries visited on this journey, Bolivia is by far the poorest with a GDP per capita one-tenth of the U.S. It is safe to assume that most of the people we met riding through the Cordillera Quimsa Cruz south of La Paz are living lives that are economically well below their average countrymen. Many are likely living on subsistence farming and are not even counted in the GDP because they generate no economic activity.

South of La Paz, we rode along the Río Choqueyapu through a valley of small farms and then climbed up the first of a number of spectacular mountain passes where people were scratching a living on ever smaller and higher terraces. Mountains and valleys fill the horizon for hundreds of miles around the snow-capped Illimani, the highest mountain in the Cordillera Real.

The road was dirt but well maintained, and we shortly came across a large road crew grading and repairing the surface. When they saw a group of gringos on large bikes, they decided that this was too good an opportunity to miss and blocked our path demanding a toll—literally, highway robbery. After a lot of back and forth we settled on 50 bolivianos (about $8), paid to the old man leading the negotiation. There were at least 20 men in this group so we have no idea how the bounty was divided up. We heard later that this likely went into a community fund, but I’m not convinced.

NO HISTORY, NO FUTURE

On our first night out of La Paz, we stayed in the guesthouse and bunkhouse on Tenería Ranch, which has been in the family of Hans Hesse for many generations. He and his family welcomed us with open arms and made a fantastic dinner of roast pork, local vegetables, and fresh bread—all from their huge outdoor baker oven.

Don Hans and I chatted for a while as a test of his patience and my Spanish. Hans was born on this farm 80-odd years ago and only spoke Aymara learned from his grandmother until age 7. He moved to La Paz to go to college and then moved to Germany where he worked for a manufacturer of heavy lifting machinery in the docks at Kiel. He retired at 46 and because pension was not paid until age 65, he moved back to the family farm where it was cheaper to live.

He told me about his four kids, his Chinese motorbike that he still rides everywhere, and the buildings on the farm that dated back 600 years. Hans bemoaned the fact that the original buildings, whose foundations still poked through the grass, had been perfectly aligned to catch the winter and summer sun on different walls, but were torn down anyway.

He then described the family memorial in the center of the property which predates the arrival of the Spanish; it was originally Aymara, then converted to Quechua, and finally extended to accommodate Catholicism to include a cross and a small niche for a statue of the Virgin Mary. Hans told me that the bones of many of his ancestors on his mother’s side are interred here, as he expects his to be when the time comes. I thanked him for taking the time to share his stories and family history. He thanked me graciously for taking an interest, ending our conversation with “Sin historia, no futura.”

LEGENDARY WINDS

There is simply not enough land mass in the narrow point of South America to slow the “Roaring Forties” winds at these latitudes of Patagonia. The winds are stronger than the same winds in the northern hemisphere because they have been blowing over water with no interruption for so long and so far. This is the most southerly bit of land that dares to poke out into these storms.

There is normally a constant 25-mph wind blowing, but riding along this part of Ruta 40 became completely impossible when the local weather service reported sustained 75-mph winds. When there was a road surface like tarmac or solid rock with some grip, it was feasible to lean the bike, but when there was fresh gravel it was impossible to resist the sideways force— you cannot lean the bike far enough without losing all grip. All of us went down or got knocked off the road. If you parked your bike with the side stand upwind, it was knocked over instantly.

Everyone seemed to invent their own technique for dealing with this: let the bike drift and then lurch upwind periodically, lean way off to windward to keep the bike vertical, go fast enough that the wheels gave more gyroscopic help—physics won every time though.

HONOR THOSE WHO SERVED

My father was conscripted in 1943 and joined the British Army Corps of Signals; he then volunteered to join the new Airborne Division. He missed the action in Europe and was sent to Palestine as part of the British Mandate and served as a Red Beret until he was demobilized in 1948. His contemporaries returned home to a hero’s welcome after the defeat of Germany, but he returned unheralded after a perceived defeat in Palestine and was never the same afterward.

Many who fought for Argentina in the Falklands War must have felt the same way. We visited the Monumento a Los Héroes de Malvinas in the naval town of Río Grande in Tierra del Fuego, Argentina. As we stopped for photographs in the cold, cutting Atlantic gale, we were greeted by José Salas who is one of 120 Malvinas veterans who maintain a vigil at the monument to honor the fallen and the veterans of this needless conflict. There is one link in the chain around this monument for each of the 648 Argentinian dead.

He handed us stickers and then led us to the museum that is self-funded by the veterans in town. We discussed his experience and that of my Dad, and he was very careful to point out that the monument and museum are not there to point blame at the British, but to remember their old friends.

FOLLOWING PLAN B

A motorbike forces a different relationship between travel and traveler. Riding requires complete commitment and concentration. The motorcycle demands that you observe your world much more closely, to soak up every detail for safety, so it all connects immediately and permanently to your cerebral cortex. Arriving on a moto creates a disturbance from the ordinary for the people we meet; it forces a conversation and creates a real personal impact. It amplifies sensations with moments of complete delight and satisfaction from conquering long distances and difficult roads, but with hundreds of moments of absolute terror, discomfort, and pain. We planned every step of the way, but it was the unplanned steps that defined our experience.

The Demon in Democracy By Ryszard Legutko

Earlier this month, Polish political philosopher Ryszard Legutko was supposed to deliver a lecture at Middlebury College in Vermont. A few hours before the event took place, college administrators called off the event, explaining the decision was based “based on an assessment of our ability to respond effectively to potential security and safety risks for both the lecture and the event students had planned in response.”

Legutko is a professor of philosophy at Jagellonian University in Krakow, Poland, specializing in ancient philosophy and political theory. He has served as a Polish government minister and a member of the European Parliament. He’s also an ardent anti-Communist with traditionalist views. That was enough, evidently, to make him a “threat” to the “safety” of Middlebury students.

Legutko gave a lecture anyway to a small group of students in a political science class. “All this was done in defiance of the college administration,” he later told the American Conservative’s Rod Dreher. “I was smuggled in a student’s car to the campus and entered the building through the backdoor.” Encounter Books editor and publisher Roger Kimball writes about the incident and its aftermath here.

In 2016, Encounter published Legutko’s latest book, The Demon in Democracy: Totalitarian Temptations in Free Societies. In it, Legutko argues that liberal democracy “tends to develop the qualities that were characteristic of Communism: pervasive politicization, ideological zeal, aggressive social engineering, vulgarity, a belief in inevitability of progress, destruction of family, the omnipresent rule of ideological correctness, and the severe restriction of intellectual inquiry.”

The following is an excerpt from that book, republished here with kind permission from Encounter.

* * *

Liberal democracy does not have and never had an official concept of history that can be attributed to a particular author. It does not have its Marx, Lenin, or Lukács. Nevertheless, from the very beginning, the liberals and the democrats made use of a typical historical pattern by which they were easily recognized and which often appeared not only in the variety of general opinions they formulated but also, on a less abstract level, in popular beliefs and stereotypes professed to be a representation of liberal thinking in mass circulation. According to this view, the history of the world—in the case of liberalism—was the history of the struggle for freedom against enemies who were different at various stages of history but who perpetually fought against the idea of freedom itself and—in the case of democracy—the history of a people’s continuing struggle for power against forces that kept them submissive for centuries. Both of these political currents—liberal and democratic—had therefore one enemy, a widely understood tyranny, which, in the long history of humanity, assumed a variety of additional, distinctive costumes. Every now and then it was a monarchy, often the Church, and at other times an oligarchy. The main enemy of freedom was portrayed in various ways in different countries and different traditions. As John Stuart Mill wrote in the passage opening his essay “On Liberty,” “The struggle between Liberty and Authority is the most conspicuous feature of history since the earliest times known to us.”

In England, at some point there emerged a Whig concept of history that was to portray the country’s basic dramatic political history. According to this view, the history of British civilization was a progressing expansion of freedom and its legal safeguards and the disappearance into the past of bad practices of autocracy or arbitrary authority beyond the control of the people and Parliament. More specifically, the history of England could be presented—as has been done many times—as a narrative of the emergence of Parliament and creation of a constitutional monarchy, with a particular legal system sanctioning it.

But the Whig view of the history of Great Britain deserves a broader look. There were also authors who treated it as a basic libertarian model of development. If one was going to introduce the idea of freedom to Western civilization, then—as they claimed—the most clearly expressed representation of the idea of freedom at its most mature, the one most rooted in law, institutions, and customs and in freedom mechanisms themselves, was revealed in the history of England. Such were the feelings of numerous Anglophiles, from the Enlightenment thinkers to Friedrich Hayek.

Naturally, a question arises of what was supposed to happen and would happen at the end of history, when freedom would claim victory over tyranny. There, for millions of people, Communism offered a rousing but actually quite vague vision. Under Communism, people were promised to have a lot of time off from work, to be free from alienation, to find employment that was rewarding and fulfilling, and to have the means of production socialized, which would result in each person receiving according to his needs. What all that was supposed to mean in more specific terms, nobody knew. When Soviet Communism emerged, some said that in fact it was precisely the system that the socialist prophets had in mind; others categorically opposed this opinion, claiming that Communism was a terrible perversion of genuine socialism, while still others argued that the Soviet regime was merely a transitional phase—somewhat unpleasant yet necessary, leading to the future realization of socialist ideals. Given the vague notions of what true socialism was supposed to be, each of these assessments was right to some extent.

The liberal vision, although less thrilling to hearts and minds, was a bit more concrete. The impetus of liberalism was understood to lie in its cooperative feature, which was to bring the human race to a higher stage of development, then called the Age of Commerce. The era of conflicts, wars, and violence—it was claimed—was coming to an end and the period of cooperation, prosperity, and progress was near. In short, the liberal era was the era of peace. This, in any case, was the way of thinking one could find in Adam Smith, Frédéric Bastiat, and other classical liberals. It does not sound particularly grand or original today, but we should remember that war was a ubiquitous experience then, and thus the prospect of peace appeared tempting if almost unrealistic and the theories that justified it had to appear exciting in their boldness.

In a famous essay, Immanuel Kant wrote about the advent of the era of “perpetual peace” among the republics. What is interesting, however, is that, according to Kant, this blessed era could and actually should be preceded by a phase of enlightened absolutism. Authors such as Spinoza, who wrote favorably about democracy, made their praise conditional on people’s first meeting high intellectual and moral requirements. They believed—and it was a fairly widespread view at the time—that tyranny, despotism, and other anachronistic regimes hindered the development of human capacity, stopping it at the early stages of dependency and helplessness. Following the removal of such regimes, work was to begin—partly resulting from a spontaneous internal desire for self-improvement of the mind and partly imposed by the enlightened rulers—that in the end would generate an improved society composed of better and more rational individuals.

A comparison between the liberal-democratic concept of the history and that of Communism shows a commonality of argument as well as of images of the historical process. Three common threads occurring in Marx’s works have their counterparts in the liberal and democratic tradition. There is a belief in the unilateralism of history, leading inevitably and triumphantly to the era of perpetual peace, or, in other terms, to the refinement of commerce and cooperation that humanity will reach due to the victory of freedom over tyranny. Another is the equivalent of deliberate human action, albeit not run by the party, but by active entrepreneurs and all types of freedom fighters, as well as the distinguished minority groups, elite and enlightened rulers who will prepare humanity—until now apathetic, enslaved, and ignorant—for the new reality. The third topic—mankind’s achieving maturity and intellectual independence—is usually described in simpler language than the German-Romantic used by the young Karl Marx and amounts to a promise of a modern society liberated from ignorance and superstition.

Over the past 150 or 200 years, the concepts of Communism, liberalism, and democracy evolved under the pressures of reality. It seems beyond doubt, however, that the first two views—that history has a unilateral pattern and that a better world is shaped by conscious human activity—are still very much present in the modern political mind.

Of course, few people talk of the laws of history today, mainly because this quasi-scientific language lost its appeal in an age when the concept of science changed. Nevertheless, both the Communists and liberal democrats have always upheld and continue to uphold the view that history is on their side. Whoever thought that the collapse of the Soviet system should have done away with the belief in the inevitability of socialism was disappointed. This belief is as strong as ever and the past practices of socialism—whether Soviet or Western—are well-appreciated, not because they were beneficial in themselves, but because they are still believed to have represented the correct direction of social change. One can observe a similar mindset among the liberal democrats, who are also deeply convinced that they represent both the inherent dynamics of social development and a natural tendency in human aspirations.

Both the Communists and liberal democrats, while praising what is inevitable and objectively necessary in history, praise at the same time the free activities of parties, associations, community groups, and organizations in which, as they believe, what is inevitable and objectively necessary reveals itself. Both speak fondly of “the people” and large social movements, while at the same time—like the Enlightenment philosophers—have no qualms in ruthlessly breaking social spontaneity in order to accelerate social reconstruction.

Admittedly, for the liberal democrats, the combination of the two threads is intellectually more awkward than for the socialists. The very idea of liberal democracy should presuppose the freedom of action, which means every man and every group or party should be given a free choice of what they want to pursue. And yet the letter, the spirit, and the practice of the liberal-democratic doctrine are far more restrictive: so long as society pursues the path of modernization, it must follow the path whereby the programs of action and targets other than liberal-democratic lose their legitimacy. The need for building a liberal-democratic society thus implies the withdrawal of the guarantee of freedom for those whose actions and interests are said to be hostile to what the liberal democrats conceive as the cause of freedom.

Thus the adoption of the historical preference of liberal democracy makes the resulting conclusion analogous to that which the communists drew from the belief in the historical privilege of their system: everything that exists in society must become liberal-democratic over time and be imbued with the spirit of the system. As once when all major designations had to be preceded by the adjective “socialist” or “Communist,” so now everything should be liberal, democratic, or liberal-democratic, and this labeling almost automatically gives a recipient a status of credibility and respectability. Conversely, a refusal to use such a designation or, even worse, an ostentatious rejection of it, condemns one to moral degradation, merciless criticism, and, ultimately, historical annihilation.

Countries emerging from Communism provided striking evidence in this regard. Belief in the “normalcy” of liberal democracy, or, in other words, the view that this system delineates the only accepted course and method of organizing collective life, is particularly strong, a corollary being that in the line of development the United States and Western Europe are at the forefront while we, the East Europeans, are in the back. The optimal process should progress in a manner in which the countries in the back catch up with those at the front, repeating their experiences, implementing their solutions, and struggling with the same challenges. Not surprisingly, there immediately emerged a group of self-proclaimed eloquent accoucheurs of the new system, who from the position of the enlightened few took upon themselves a duty to indicate the direction of change and to infuse a new liberal-democratic awareness into anachronistic minds. They were, one would be tempted to say, the Kantian Prussian kings of liberal democracy, fortunately devoid of a comparable power, but undoubtedly perceiving themselves to have a similar role as pioneers of the enlightened future.

In their view, today also consciously or unconsciously professed by millions, the political system should permeate every section of public and private life, analogously to the view of the erstwhile accoucheurs of the communist system. Not only should the state and the economy be liberal, democratic, or liberal-democratic, but the entire society as well, including ethics and mores, family, churches, schools, universities, community organizations, culture, and even human sentiments and aspirations. The people, structures, thoughts that exist outside the liberal-democratic pattern are deemed outdated, backward-looking, useless, but at the same time extremely dangerous as preserving the remnants of old authoritarianisms. Some may still be tolerated for some time, but as anyone with a minimum of intelligence is believed to know, sooner or later they will end up in the dustbin of history. Their continued existence will most likely threaten the liberal-democratic progress and therefore they should be treated with the harshness they deserve.

Once one sends one’s opponents to the dustbin of history, any debate with them becomes superfluous. Why waste time, they think, arguing with someone whom the march of history condemned to nothingness and oblivion? Why should anyone seriously enter into a debate with the opponent who represents what is historically indefensible and what will sooner or later perish? People who are not liberal democrats are to be condemned, laughed at, and repelled, not debated. Debating with them is like debating with alchemists or geocentrists. Again, an analogy with Communism immediately comes to one’s mind. The opponents of Communism—e.g., those who believed free markets to be superior to planned economies—were at best enemies to be crushed, or laughingstocks to be humiliated: how else could any reasonable soul react to such anachronistic dangerous ravings of a deluded mind?

After all, in a liberal democracy everyone knows—and only a fool or a fanatic can deny—that sooner or later a family will have to liberalize or democratize, which means that the parental authority has to crumble, the children will quickly liberate themselves from the parental tutelage, and family relationships will increasingly become more negotiatory and less authoritarian. These are the inevitable consequences of civilizational and political development, giving people more and more opportunities for independence; moreover, these processes are essentially beneficial because they enhance equality and freedom in the world. Thus there is no legitimate reason to defend the traditional family—the very name evokes the smell of mothballs—and whoever does it is self-condemned to a losing position and in addition, perpetrates harm by delaying the process of change. The traditional family was, after all, part of the old despotism: with its demise, the despotic system loses its base. The liberalization and democratization of the family are therefore to be supported—wholeheartedly and energetically—mainly by appropriate legislation that will give children more power: for example, allowing increasingly younger girls to have abortions without parental consent, or providing children with legal instruments to combat their claims against their parents, or depriving parents of their rights and transferring those rights to the government and the courts. Sometimes, to be sure, these things can lead to excessive measures perpetrated by the state, law, and public opinion, but the general tendency is good and there is no turning back from it.

Similarly, in a liberal democracy, everyone knows—and only a fool or a fanatic can deny—that schools have to become more and more liberal and democratic for the same reasons. Again, this inevitable process requires that the state, the law, and public opinion harshly counteract against all stragglers—those who are trying to put a stick in the spokes of progress, dreamers who imagine that in the twenty-first century we can return to the school as it existed in the nineteenth, pests who want to build an old-time museum in the forward-rushing world. And so on, and so forth. Similar reasoning can be applied to churches, communities, associations.

As a result, liberal democracy has become an all-permeating system. There is no, or in any case, cannot be, any segment of reality that would be arguably and acceptably non-liberal democratic. Whatever happens in school must follow the same pattern as in politics, in politics the same pattern as in art, and in art the same pattern as in the economy: the same problems, the same mechanisms, the same type of thinking, the same language, the same habits. Just as in real socialism, so in real democracy, it is difficult to find some nondoctrinal slice of the world, a nondoctrinal image, narrative, tone, or thought.

In a way, liberal democracy presents a somewhat more insidious ideological mystification than Communism. Under Communism, it was clear that Communism was to prevail in every cell of social life, and that the Communist Party was empowered with the instruments of brutal coercion and propaganda to get the job done. Under liberal democracy, such official guardians of constitutional doctrine do not exist, which, paradoxically, makes the overarching nature of the system less tangible, but at the same time more profound and difficult to reverse. It is the people themselves who have eventually come to accept, often on a preintellectual level, that eliminating the institutions incompatible with liberal-democratic principles constitutes a wise and necessary step.

Forty years ago, at the time when the period of liberal-democratic monopoly was fast approaching, Daniel Bell, one of the popular social writers, set forth the thesis that a modern society is characterized by the disjunction of three realms: social, economic, and political. They develop—so he claimed—at different rates, have different dynamics and purposes, and are subject to different mechanisms and influences. This image of structural diversity that Bell saw coming was attractive, or rather would have been attractive if true. But the opposite happened. No disjunction occurred. Rather, everything came to be joined under the liberal-democratic formula: the economy, politics and society, and—as it turns out—culture.

Saturday, April 27, 2019

Governor J.B. Pritzker: Hypocrite of the Year April 27, 2019 by Dan Mitchell

If the people who advocate higher taxes really think it’s a good idea to give politicians more cash, why don’t they voluntarily send extra money with their tax returns?

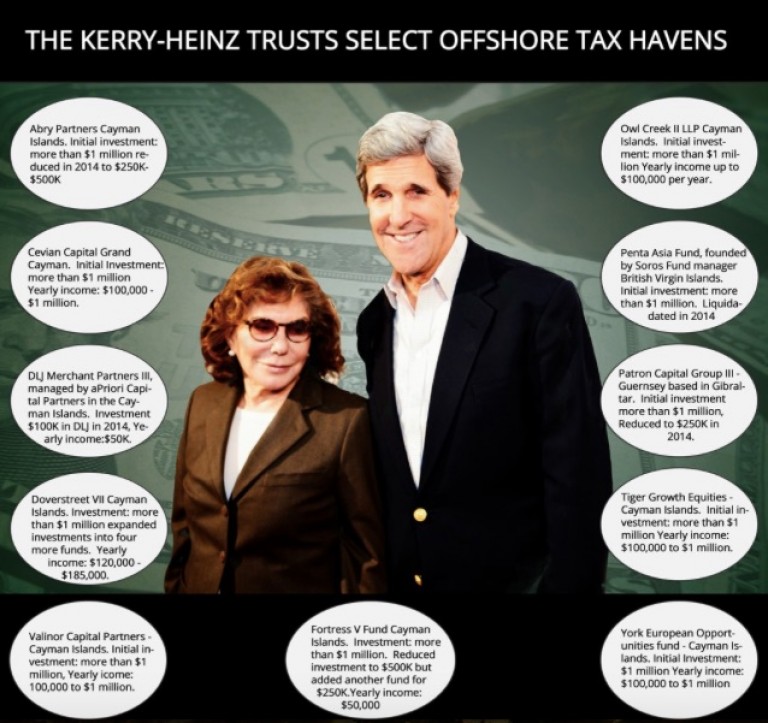

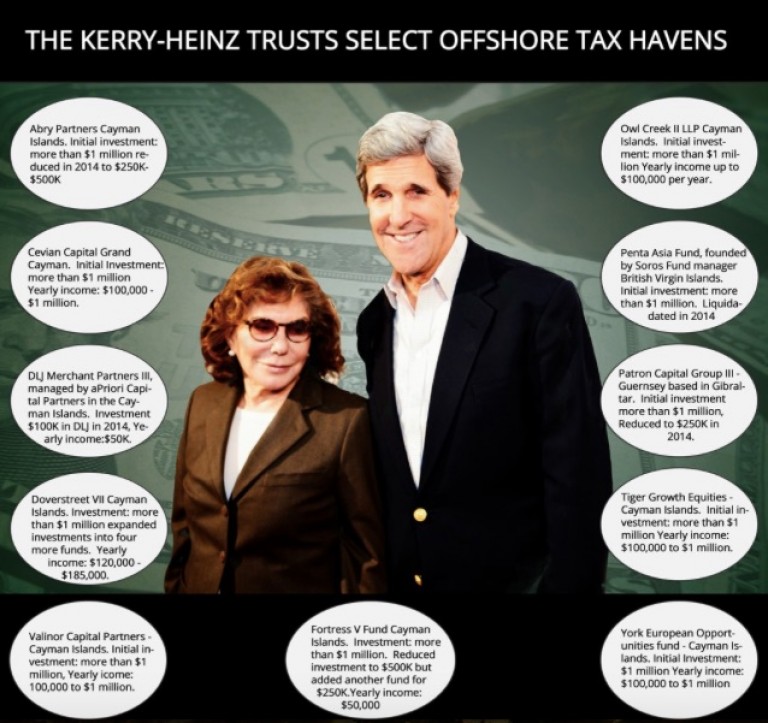

Massachusetts actually makes that an easy choice since state tax forms give people the option of paying extra,  yet tax-loving politicians such as Elizabeth Warren and John Kerry never avail themselves of that opportunity.

yet tax-loving politicians such as Elizabeth Warren and John Kerry never avail themselves of that opportunity.

yet tax-loving politicians such as Elizabeth Warren and John Kerry never avail themselves of that opportunity.

yet tax-loving politicians such as Elizabeth Warren and John Kerry never avail themselves of that opportunity.

And the Treasury Department has a website for people who want to give extra money to the federal government, yet proponents of higher taxes (at least for you and me) never lead by example.

For lack of a better phrase, let’s call this type of behavior – not choosing to pay extra tax – conventional hypocrisy.

But what about politicians who support higher taxes while dramatically seeking to reduce their own tax payments? I guess we should call that nuclear-level hypocrisy.

And if there was a poster child for this category, it would be J.B. Pritzker, the Illinois governor who is trying to replace his state’s flat tax with a money-grabbing multi-rate tax.

The Chicago Sun Times reported late last year that Pritzker has gone above and beyond the call of duty to make sure his money isn’t confiscated by government.

…more than $330,000 in property tax breaks and refunds that…J.B. Pritzker received on one of his Gold Coast mansions — in part by removing toilets…Pritzker bought the historic mansion next door to his home, let it fall into disrepair — and then argued it was “uninhabitable” to win nearly $230,000 in property tax breaks. …The toilets had been disconnected, and the home had “no functioning bathrooms or kitchen,” according to documents Pritzker’s lawyers filed with Cook County Assessor Joseph Berrios.

Wow, maybe I should remove the toilets from my house and see if the kleptocrats in Fairfax County will slash my property taxes.

And since I’m an advocate of lower taxes (for growth reasons and for STB reasons), I won’t be guilty of hypocrisy.

Though Pritzker may be guilty of more than that.

According to local media, the tax-loving governor may face legal trouble because he was so aggressive in dodging the taxes he wants other people to pay.

Democratic Illinois Gov. JB Pritzker, his wife and his brother-in-law are under federal criminal investigation for a dubious residential property tax appeal that dogged him during his gubernatorial campaign last year, WBEZ has learned.…The developments demonstrate that the billionaire governor and his wife may face a serious legal threat arising from their controversial pursuit of a property tax break on a 126-year-old mansion they purchased next to their Gold Coast home. …The county watchdog said all of that amounted to a “scheme to defraud” taxpayers out of more than $331,000. …Pritzker had ordered workers to reinstall one working toilet after the house was reassessed at a lower rate, though it’s unclear whether that happened.

This goes beyond nuclear-level hypocrisy – regardless of whether he’s actually guilty of a criminal offense.

Though he’s not alone. Just look at the Clintons. And Warren Buffett. And John Kerry. And Obama’s first Treasury Secretary.  And Obama’s second Treasury Secretary.

And Obama’s second Treasury Secretary.

And Obama’s second Treasury Secretary.

And Obama’s second Treasury Secretary.

Or any of the other rich leftists who want higher taxes for you and me while engaging in very aggressive tax avoidance.

To be fair, my leftist friends are consistent in their hypocrisy.

They want ordinary people to send their kids to government schools while they send their kids to private schools.

And they want ordinary people to change their lives (and pay more taxes) for global warming, yet they have giant carbon footprints.

P.S. There is a quiz that ostensibly identifies hypocritical libertarians.