The mission was simple on paper, but daunting in execution. Rogers’s rangers were ordered to “attack the enemy’s [Indian] settlements on the south side of the river St. Lawrence in such a manner as you may judge most effective.” The rangers would have to travel approximately 160 miles through some of the roughest wilderness in North America, yet also escape detection from the French and their Indian allies in the area. They would also have to maintain an element of surprise.

“Rogers’ Rules of Ranging”

The raid was the brainchild of Rogers, an American frontiersman who was born in New Hampshire. He was raised on the borderlands, a wilderness area bitterly contested by England and France in a series of bloody colonial conflicts. It was a rough school, but Rogers soon became adept at surviving in the hostile environment. By the time he was in his early 20s, he was a seasoned frontiersman, tall (over six feet), tough, and thoroughly knowledgeable in the ways of the wilderness.

Rogers did not invent the ranger idea, which had been around since the Indian wars of the late 17th century, but he did codify the concept with a series of well-thought out “commandments” he called “Rogers’ Rules of Ranging.” His exploits made him famous, but his rules—a kind of field manual—proved even more enduring. Over time, he assumed control of the various ranging companies, although technically he was only a captain in command of his own personal company. These groups became known collectively as Rogers’ Rangers, but they were in fact independent companies in loose association with him. There was never an officially recognized unit called “Rogers’ Rangers” on British muster rolls.

The Capture of Captain Quinton Kennedy

British morale was at a low ebb when William Pitt became prime minister is 1757. Pitt soon grasped the importance of America in Great Britain’s quest for victory over France. Fresh troops, ships, and supplies came streaming over the Atlantic. Maj. Gen. Jeffrey Amherst, methodical and competent, became the new commander in chief for America. Pitt envisioned nothing less than an all-out coordinated attack on French Canada, with rapier-like thrusts into the very heart of New France.

Amherst proceeded with caution, and his first moves met with success. Fort Ticonderoga was taken, finally removing a painful thorn from the British paw. The French also abandoned Fort St. Frederic, which the British renamed Crown Point. But then Amherst’s natural caution took over. The offensive had begun well but run out of steam. Precious summer months, with the best weather for campaigning, were rapidly slipping away.

Hungry for news from the north, Amherst dispatched Captain Quinton Kennedy of the 17th Foot to try and get through to other British commanders. Kennedy’s party included another British officer and several Mohican Stockbridge Indian warriors. But Kennedy was more than just a courier; he was also empowered to offer peace to French-allied Indians along the way, particularly the fierce Abenaki. Kennedy’s peace mission may have been a ruse, a way to get through hostile Indian territory and establish contact with other British commanders. If so, the trick failed, and Indian warriors captured Kennedy and all his party. French General Louis-Joseph, Marquis de Montcalm, wrote a letter to Amherst expressing surprise that two regular British officers had been caught out of uniform. The pair was clapped in irons, but otherwise well treated.

Amherst was furious when he heard of Kennedy’s capture, claiming the officer had been operating under a flag of truce. Unhappy and frustrated, Amherst was in the mood for revenge. The capture of his emissaries was the last straw—the Indians must be taught a lesson. Robert Rogers stepped forward, suggesting a plan that had been in the back of his mind of some time, a raid on St. Francis, one of the principal strongholds of the Abenaki near the St. Lawrence River.

St. Francis: A Jesuit Mission

St. Francis—more properly St. François de Sales—was originally established opposite Quebec, but it was relocated near the St. Francis River in 1700. It was a Jesuit mission, and many of the Indians were at least nominal Catholics. The Jesuits, called the Black Robes because of their clerical garb, were successful because they sanctioned, or at least tolerated, many Indian traditional ways. The St. Francis settlement soon developed a reputation for savagery. Raiding parties poured out of St. Francis, attacking English settlements throughout the New England frontier. Men, women, and children were massacred and scalped, their hair proudly displayed as trophies at St. Francis. The settlement harbored the broken remnants of many tribes, although the Abenaki had become the dominant force at the mission. There were also Pennacook, Montagnais, Micmac, and Nipmucs, the latter originally from New England.

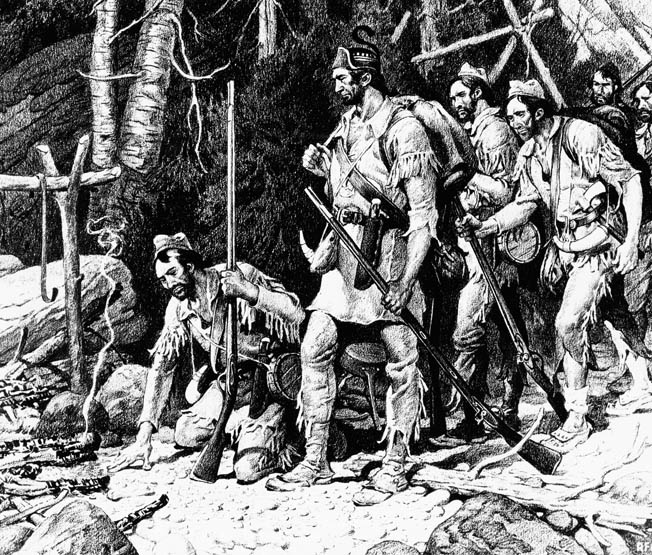

Period engraving of Robert Rogers.

Rogers was happy when Amherst green-lighted his expedition, but he faced the immediate problem of obtaining recruits. The St. Francis raid was going to be most difficult, and there was a critical lack of seasoned backwoodsmen. Years of incessant frontier war had taken a heavy toll on the rangers. Rogers found new recruits among the provincial militia. Some British regulars also joined the expedition, particularly Light Infantry, Scots from the Royal Regiment, and the famed “Black Watch” 42nd Highlanders. The Rangers would also be accompanied by Stockbridge Indians from the Mohican tribe who had already performed invaluable services as scouts and auxiliaries.

The Way to St. Francis

After the raiders left Crown Point, the first goal was Missisquoi Bay, 80 miles to the north. Lake Champlain was fairly narrow in the early stages, and there was a distinct possibility that the rangers might be detected by a French flotilla that regularly scoured the waters. The French schooner La Vigilant and a trio of sloops were constantly on the lookout for British incursions. The expedition would row all night, then come ashore to hide in the lake’s marshy rim during the day.

Within a few days, a steady stream of sick and injured men began to limp back to Crown Point. Rogers lost 41 men to disease or accident, about a fifth of his overall command. Rogers’s luck held, however, and the raiders escaped detection by the French gunboats. The lake widened and the whaleboats took the channel to the east of the island, crossing a sandbar that would prevent larger vessels from following.

As they neared Missisquoi Bay, the weather turned stormy. The placid lake boiled with white water, and the rangers’ fragile whaleboats were buffeted by waves, rain, and bone-chilling winds. Even after the rangers reached shore, their ordeal was not over. It was bitterly cold, yet they could not light fires for fear of discovery. Huddled in sodden blankets, wet to the skin, they could only shiver and wait for the dawn.

The rest of the journey would be on foot. The whaleboats were carefully concealed, together with a cache of supplies for the return trip. The rangers left Missisquoi Bay on September 23, leaving behind two Indian scouts to keep an eye on the whaleboats. The force headed in an easterly, then northeasterly track to avoid the French and their Indian allies. Progress was slow, perhaps 10 miles a day, because the rangers were passing through spruce bogs that made walking difficult.

Crossing the St. Francis River

Grimy and exhausted, the rangers were still at the beginning of their ordeal. The two Indian scouts suddenly appeared with unwelcome news: the French had found the whaleboats. Alarms were dispatched, and large parties of French and Indians were sent to intercept the raiders. Logic dictated that the expedition be aborted, but Rogers had no intention of abandoning his plans. He would destroy St. Francis, then retreat on foot though some of the roughest country in New England.

Rogers sent Lieutenant Andrew McMullen back to Crown Point with a message for General Amherst, asking him to send supplies to the Ammonoosuc River near where it enters the Connecticut. Roger explained that he would return there—if he returned at all. The cream of the Abenaki fighting forces joined French militia to wait in ambush for Rogers and his men.

Rogers and the rangers had been lucky so far, but the major was not one to rest on his laurels. The next obstacle was the raging St. Francis River. The rangers were on the south side of the river, while their objective was on the north. The raging torrent had to be forded—but how? Rafts were out of the question, because wood chip debris from felled trees might float downstream and give a warning to St. Francis. Axes or hatchets would also make noise as they bit into the wood.

Rogers quickly came up with a solution. He formed some of the men into a human chain, gripping each other tightly, link by link. The river was about five feet deep at this point, the current swift. A man who lost his footing would find his head fully submerged, only to come up sputtering and gasping. The human chain was a success and the entire command managed to cross without any loss of life. The men were sodden but elated—the village was only a few hours’ march away. Still, the journey had taken a heavy toll on the rangers. Most looked more like tramps than soldiers or woodsmen. Their clothing was dirty, torn, and ragged, and scraggly beards darkened their faces. Above all, the rangers were starving. It was desperately hoped that food might be found at St. Francis.

Rogers Reconnoiters in the Town

The rangers reached the outskirts of the village on October 3, and Rogers thought it best to reconnoiter. Around 8 pm, he and two other rangers entered St. Francis to glean what information they could. It seems incredible that Rogers could so freely enter an enemy village, but in this case the danger was more apparent than real. Saint Francis was a polyglot settlement, with people coming and going at all times. English captives could often be seen there, and French-Canadian trappers and hunters frequented the place. Rogers spoke fluent French, so his mere presence would not arouse suspicion. To further conceal his visit, when Rogers arrived, St. Francis was in the midst of a giant celebration, possibly a wedding.

Rogers and his two companions were surprised to see what St. Francis really looked like. It was no rude collection of birch bark huts, but rather a sturdy town with buildings more reminiscent of provincial France than the American frontier. The settlement boasted some 60 dwellings in all, many featuring windows, lofts, and cellars, clustered around a village square dominated by a Jesuit Catholic Church. There was also a council house with musket loopholes in its walls. Yet amid all the European trappings, there were still signs of Abenaki ferocity. Some 600 scalps, most of them English, were displayed around the village on trophy poles.

ca. 1800s — Vermont: A tragic episode in the retreat of Rogers’ half-starved Rangers took place at the mouth of the Passampsii in Vermont in 1759. A rescue party with provisions was encamped there to await the return of Rogers’ Expedition against St. Francis Indians in Canada. Hearing rifle fire up the river, and fearing an Indian attack, the rescue party fled south in canoes taking all provisions with them. The half-dead Rangers arrived to find the ashes of the camp fire still warm, but not a crumb of food. Unable to go further, many of the Rangers died of starvation.

The St. Francis Raid

Rogers’s plan for attack was simple but effective. They would pounce on the village in three divisions, converging on the target from the south, east, and north. Amherst’s orders were clear: revenge could be taken, but Indian women and children were to be spared. Unfortunately, the semi-darkness, coupled with the excitement and fever of battle, meant that deadly mistakes were bound to be made.

The assault began at 5 am, an hour before dawn. By then the celebration was over, and the exhausted revelers had returned to their homes to sleep. The village was completely surprised; no sentries had been posted. Once inside the village, the rangers fanned out, entering homes to kill every fighting warrior they could find. Resistance was easily overcome. Once the last shot was fired., the rangers put the village to the torch, burning French-style houses and Indian wigwams alike. High-pitched screams rose above the crackling flames. For those Indians taking shelter in lofts and cellars, their hiding places had become funeral pyres.

The rangers took a number of Indian captives, including Marie-Jeanne Gill and her two sons. Her husband was blond-haired Chief Joseph-Louis Gill, himself born of white captive parents at St. Francis. Marie-Jeanne, despite her French name, was a full-blooded Abenaki, the daughter of a principal chief. The raid also freed some white captives, including George Barnes of New Hampshire, a German woman from Dutch Flats, and three rangers who had been taken some time before.

One white captive, Jane Chandler, did not want to be rescued. Taken when she was about five, she had been adopted into the tribe and was now thoroughly native. Her Abenaki husband had been killed in the raid, and she was in no mood to be cooperative. On the journey back she purposely tried to get one party lost. The rangers’ Mohican allies had little patience with such tactics and threatened to slit the woman’s throat. They became distracted while squabbling over some corn, and Chandler made her escape.

Rogers later claimed that he had killed 200 Indians at St. Francis, but best estimates of the total village population placed it at 500 souls. Most of the warriors were away at the time, so the village population must have been smaller. The French claimed that around 40 villagers had been killed, most of them women and children.

An Exhausting Six Weeks for “the White Devil”

Nevertheless, Rogers had accomplished his mission. The task now was to get home. Rogers and the rangers departed the ruins of St. Francis at about 11 the next morning. For the next eight days they marched until they reached the vicinity of Lake Memphremagog. Rations were short, the men were starving, and game was scarce. Rogers decided to break his men up into small groups, each with a reliable guide. It was a fateful decision, and one that would prove fatal for some groups. The major was a resourceful leader, but even he could not conjure up food in an empty wilderness.

The ensuing journey was a waking nightmare. Famished rangers ate everything they could find, including bark, beech leaves and small amphibians. Others consumed their belts and shoes, and even boiled their powder horns in a vain quest for nourishment. Exhausted beyond human endurance, they somehow kept moving toward the rendezvous point on the Ammonoosuc River. But when the rangers finally reached their goal, bitter disappointment awaited them. No one was there, although a smoldering campfire showed there had been recent visitors. Lieutenant Samuel Stevens had been dispatched by Amherst with food and supplies, but after waiting a few days, Stevens grew uneasy and returned to Crown Point. Supposedly he saw signs of Rogers’ approach and thought it was the enemy. He missed Rogers and the rangers by two hours.

This was the last straw. The men simply could not go on any further. Summoning his last reserves of strength, Rogers left to get help with Captain Amos Ogden and Antoine, one of Chief Gill’s captive sons. The major’s goal was British Fort Number 4, 60 miles away. Somehow Rogers and his party reached the fort. By then, Rogers was in such poor shape he could scarcely walk, but he insisted on going back to the rendezvous point with the food his men so desperately needed. After more than six weeks of hardship, bloodshed, heroism, and savagery, the St. Francis Raid was over.

Rogers was celebrated for his wilderness skills, courage, and fortitude in the face of adversity. For the Abenaki, however, Rogers was anything but a hero. The major may not have actually killed many warriors, but his raid was a great psychological victory over the Abnenaki and their allies. His daring exploits gained him a new title among his Indian foes. To them and their descendants, he was Wobi Madaonodo—“the White Devil.”

No comments:

Post a Comment