For many years the trail up the East Fork of the Bitterroot River avoided the narrow rocky canyon above Medicine Springs, and followed Spring Gulch up to a low saddle north of Sula Peak.

This is the same trail that Lewis and Clark used after leaving the Salish Indian encampment near Sula in 1805, and the same trail many settlers here in the valley followed as they made their way over to the Big Hole Valley and various other points east of the divide.

According to the recollections of Herbert ‘Bertie’ Lord, early pioneers had often speculated as to whether a wagon road could be built along the river up through the rugged canyon, and in 1878 a team of experts was sent out from Missoula to investigate the possibility.

In a letter Bertie wrote to the editor of a local newspaper years later, he provided a detailed account of the excursion, with most of his information coming from conversations he overheard between his father Ed, and W. B. Harlan, a key figure in the escapade.

Bertie’s letter stated that for a number of years there had been “considerable talk about building a wagon road from the Bitter Root to Bannack. Finally, the county commissioners (this was part of Missoula County then) decided to send some viewers over the part of the road that would be in this county and make a report about the condition and whether it was feasible to build the road or not. At that time the old Indian Trail came up the East Fork all the way on the north side to avoid crossing the river. W. B. Harlan was one of the three viewers appointed to look over the route and report their findings to the county commissioners at Missoula.”

The Lord family ranch was situated on the East Fork of the Bitterroot, near the mouth of Warm Springs Creek, just across the river from a favorite campsite used by the Salish Indians, known as Rattlesnake Flat. Bertie relates that in those days the old trail forked at the flats, the one on the north side followed Spring Gulch up over the saddle into Ross Hole, and the other less-used route traced the river up through the rocky canyon. He goes on to say that when Mr. Harlan and his fellow viewers got up the river to Rattlesnake Flat they found old Delaware Jim and some Salish Indians encamped there.

The surveyors asked Delaware Jim about the conditions in the canyon from there to Ross Hole, and if he thought a wagon road could be built through it. “Well,” says Delaware Jim, “you won’t have much trouble until you get about half way to Ross Hole. When you come to a big rock, then you have hell.”

‘Delaware Jim’ Simonds was a Delaware Indian who reportedly had served along with his father as a hunter with the John C. Fremont Expedition in the spring of 1843. Afterwards, Jim and his brother Ben offered their services along the Emigrant Road during the summers, and often wintered in the Beaverhead or Bitter Root valleys of Montana, bringing along a wide variety of goods to trade with the local Indians.

Throughout the 1850s Major John Owen hired Jim to accompany him as hunter on many of his purchasing ventures from Fort Owen, and his name appears repeatedly in Owen’s journals. Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens even relied on Delaware Jim once as a hunter, guide and interpreter during the Blackfoot Council near Fort Benton. He also served as interpreter later on during the Nez Perce War, when soldiers from Fort Missoula built the futile barricade known as Fort Fizzle, in Lolo Canyon.

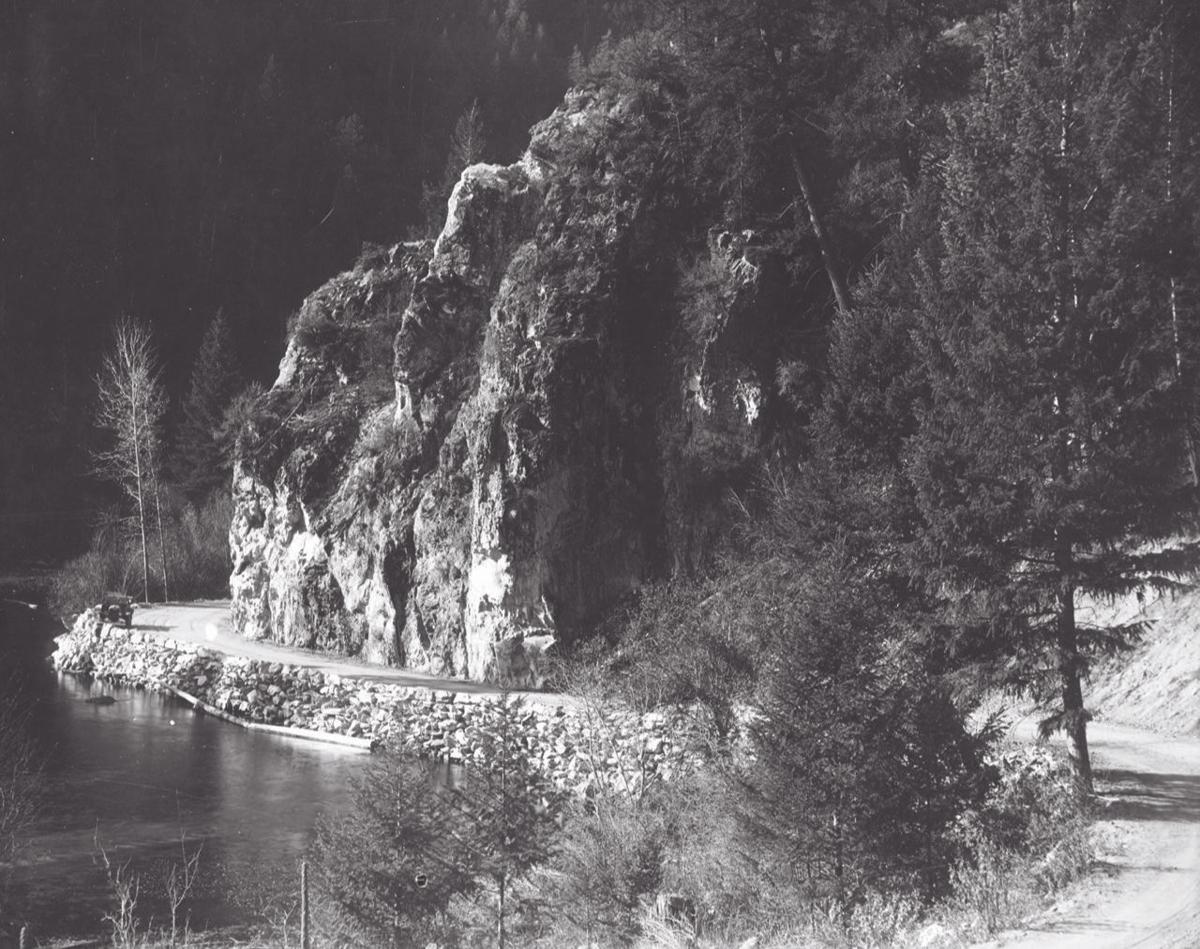

Getting back to the story of Jim Hell Rock, we again turn to the recollections of Bertie Lord, who says that when the survey crew got a little further up the canyon, “they found the big rock all right, and the river was running along side and against the base of the rock. A good sized tree that had been growing on the opposite side of the river had been undermined by high water and had fallen across the river and landed against the big rock and was there in a slanting position with the top a few feet up the rock. Mr. Harlan climbed up this leaning tree until he reached the face of the cliff where the tree had lodged, and with a fire coal wrote the words Jim’s Hell.”

The inscription was positioned just under a kind of an overhang on the rock so it had some protection from the weather. The writing could be plainly seen for several years after Bertie came to the valley in 1882, and he used to look at it every time he went up or down the canyon.

Apparently Mr. Harlan thought the construction project was worth doing, so the contract to build a wagon road stretching from the upper valley through Ross Hole and over the divide at Gibbons Pass was given to Joseph Pardee in 1879, for the sum of $1,100. However, the contract did not include the cost of building any bridges over the East Fork, and the new road had to crisscross the river a number of times as it wound its way up through the narrow rocky gorge.

Once the road was built through the canyon, there were six fords on the river, and two of them were at Jim Hell Rock. One was just below the towering cliff, and the other was about 100 yards above it. Both fords were eliminated a few years later when another man was paid $200 to bring in fill material and build up the road right next to the rock. Bertie says that one of the best fishing-holes on the East Fork was lost in the process.

Bertie’s father kept a regular journal, and in it he says that he and several other East Fork residents worked on the road around Jim Hell Rock in the spring of 1895. They also worked on shoring up the few bridges that existed at the time along that stretch of the river. In August Ed Lord reported that Bertie “threw rocks out of the road from above Jim Hell Rock up to Ross Hole,” and he also noted that in September while he was working on the road, Bertie “came up and took a picture of the rock.”

I can’t go on without mentioning an unusual story, which admittedly has only a minimal connection to Jim Hell Rock, but is worth retelling just the same. Again, my main source for the following material is Bertie Lord, who would have been about 13 years old at the time. Bertie recalls that in the spring of 1883, Sig Chaffin gathered up about 300 hogs that belonged to a group of farmers from around Corvallis, and drove them to Ross Hole to pasture for the summer. Bertie was living with his father and uncle at Billie Edwards’ ranch on Rye Creek when the oddball procession passed through.

“I saw them go by, as the road was close to the house where we were living on the Edwards’ place. I also saw the hogs go back in the early fall. Sig and Alex and, I think, Mose (Chaffin) was with them, and I don’t remember whether there was anyone else or not. I have heard Sig and Alex talk a good many times about their experiences with that bunch of hogs that summer and I guess it was a headache from start to finish and they never tried it again.” Bertie says that Sig Chaffin earned a $1 per head to care for the squealing herd of swine that summer, and that “the hogs had to live on grass and camas and whatever vegetation they could find on the flats of Ross Hole, and I don’t think they got fat on it, but they lived anyway.”

Apparently the passel of porkers had to ford the river 13 times between Corvallis and Ross Hole, and when they got to Rattlesnake Flat the herders followed the old Indian trail up Spring Gulch. The old trail was still utilized during high water, when the spring runoff would often completely fill the narrow canyon of the East Fork, and flood over the newly constructed road. No bridges were built across that stretch of the river until several years after the road was completed.

When the entourage finally got into Ross Hole, the men couldn’t keep their herd together any longer, and in no time at all the headstrong hogs were spread out “all over the basin.” At the end of the summer, our savvy swine-herders drove their unruly oinkers’ back to the Bitterroot, leading them down through the canyon where they passed over the ridge just behind Jim Hell Rock. Gathering up that extraordinary herd of hogs must have made for quite a memorable roundup!

These days the only herds navigating the rocky canyon are a curious batch of bighorn sheep that are often found standing right in the middle of the road. Today’s hurried traveler flies through the canyon past Jim Hell Rock without ever realizing just how drastically things have changed over time.

The river no longer laps at the sheer rock wall as it did for endless generations before the road was built, and the rustic charcoal inscription placed there by W. B. Harlan has long since disappeared. The wide modern highway sweeps by close to the stony escarpment in a way that was once reserved only for the icy waters of the East Fork, but if you look closely on your way back from Sula, you can still see the perfectly placed retaining wall that was carefully built up more than a hundred years ago.

And if you happen to slow down a little bit, and cast a passing glance at your rugged surroundings, you can almost imagine exactly what it was that Delaware Jim was talking about.

No comments:

Post a Comment