The trail that crosses the Continental Divide at Gibbons Pass has been utilized for countless centuries by Native Americans on their frequent sojourns to and from the Bitter Root Valley.

In fact, the Salish Indians were preparing to cross the mountains over this very pass on the way to their fall buffalo hunt when Lewis and Clark met them in September of 1805. The following year Captain Clark and his men used the same gap in the mountains to return to their canoes and supplies that they had stashed at Camp Fortunate on the upper reaches of the Jefferson River.

For some time afterwards the low saddle crossing the divide was actually known as Clark’s Pass, until General John Gibbon used it in 1877 during the Nez Perce War. It seems likely that buffalo herds also filtered into the Bitter Root Valley over the same pass in prehistoric times, and Captain Clark actually reported seeing old dried buffalo skulls strung out along the well-used trail he followed when he crossed over to the Big Hole Valley in the summer of 1806.

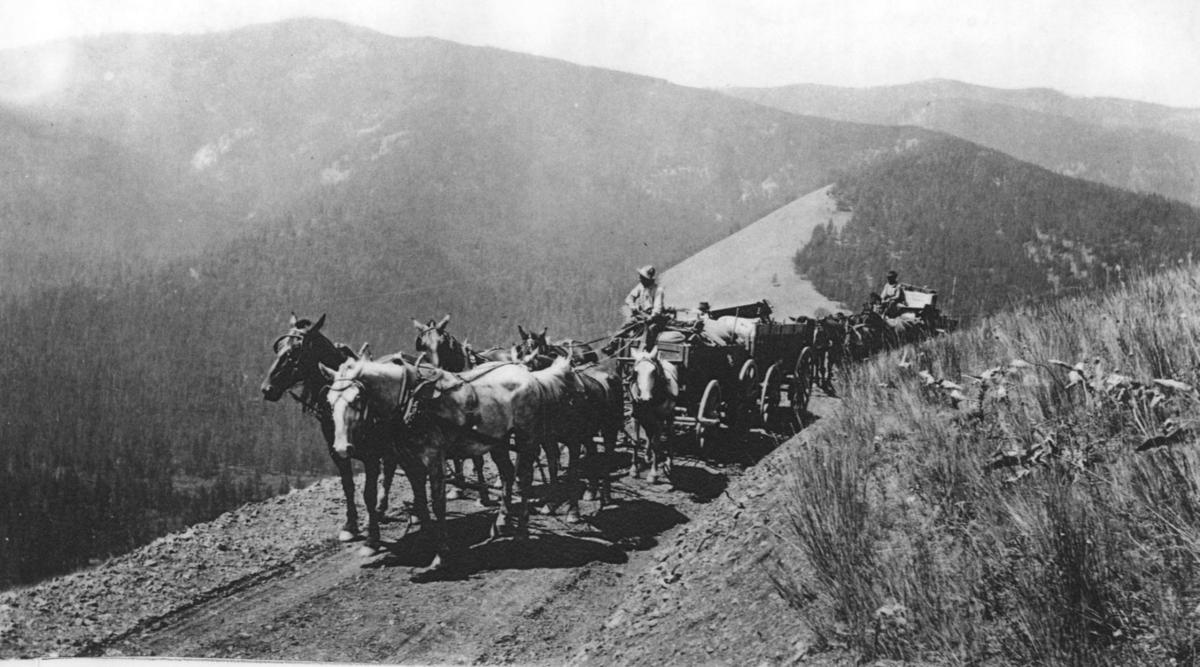

Eventually a rough wagon road was hewed out over the pass so that produce from the Bitter Root could be transported over to the mining camps around Bannack and Virginia City. The steep slope on the west side of the mountain had presented quite a problem for teamsters bringing goods in and out of the valley since the 1850s.

The first Forest Service road built in the district was the Big Hole Road, which crossed from Camp Creek in the Sula Basin, over to the Big Hole Battlefield west of Wisdom.

In 1914 Nathaniel E. Wilkerson, a district forester who had been with the Bitter Root Forest Reserve since its inception in 1897, was assigned the job of surveying and overseeing the construction of the mountainous road which would link the two valleys. Frank Bonner, who was a district engineer out of Missoula, was chosen to aid and assist “Than” Wilkerson on the road survey and grade calculations.

The road was 26.6 miles long and followed the natural contours of the mountain, and for the most part avoided the rockiest portions of the hillside. It cost $52,000 to survey and construct the road, with funds coming from the U.S. Forest Service, Ravalli and Beaverhead County taxpayers, and various other private investors and supporters of the project.

According to Wilkerson the first car to travel the road was driven by Dr. Herbert Hayward and Al Rissman.

At the time Hayward was a practicing physician in Darby, and Rissman operated a pharmacy there. While the road was being built Dr. Hayward had been treating the workers who toiled relentlessly on the steep grades of the mountain trail. Many of the workers were Bulgarians and Montenegrins from the Butte mines that had also worked on local projects, such as the Lake Como Dam and the Big Ditch, just a few years earlier.

The first quarter-mile of roadway was leveled off with horses and scraper blades, but after that the job had to be tackled by laborers wielding picks and shovels. Mr. Wilkerson estimated the grade at 5% on the 7½ miles that made up the western slope, and the ground was mostly decomposed granite, which made for an incredibly hard and durable roadbed.

The work was paid out on a yardage basis, and the road was measured up in 100-foot sections. A worker received 40 cents a yard for moving dirt, and the average pay was about $2 a day! The Beaverhead County portion of the road was more gently sloping, and horses and grader blades were used to level that section of the road.

As the project neared completion, the towns of Darby and Wisdom were becoming extremely excited at the prospect of finally being linked together by a functional roadway, and the Wisdom Chamber of Commerce invited their Bitter Root neighbors to send a pilot car over the new road as soon as possible.

Dr. Hayward had a brand new Ford runabout and he and Al Rissman decided to make the crossing in September of 1914. On the appointed day the two men lashed a couple of 2x12 planks onto the sides of the motorcar and set out upon their maiden voyage. Meanwhile, the citizens of the Big Hole Valley eagerly awaited the expected arrival of the adventurous motorists later that day.

No sooner had the car started its ascent of the west slope than the cooling system began to boil over, and the men had to stop periodically to climb down to a creek to get water for the radiator. This process was repeated over and over until the motorists got too tired to fetch water and decided to wait for the brisk mountain air to cool the red-hot engine.

It was just about dusk when the trailblazers neared the top of the mountain where Ravalli County ends and Beaverhead County begins. Then, just before reaching the summit, the car hit a stump that knocked the oil pan drain plug loose, causing the engine to loose all of its motor oil! The men ate a hearty steak supper at the road workers camp that was situated near the summit, while the camp’s blacksmith fabricated a wooden plug that would hopefully seal up the leaky oil pan.

The plug worked, but the unprepared tourists had neglected to bring any spare oil along with them. Luckily, the ingenious camp cook provided them with enough cooking oil to once again get them on their way!

It was dark when the men left the camp and started to make their way down the old Trail Creek Road. After a couple of miles the duo came out onto a large prairie where they hit a big rock in the road, which damaged the vehicle’s steering mechanism. They spent the night in an old abandoned cabin with no heat and no warm blankets. Early in the morning they found enough tools in the car to get the damaged part off, and then used rocks to pound it back into good enough shape to steer the car!

By sunup they were on the road again, crossing Trail Creek back and forth using their 16 foot-long planks to drive on. At Ruby Creek the car slid off the planks and got mired down in the muck. Fortunately, a cowboy came along who offered to lasso the bumper of the car and pull it out of the mire with his horse. When the car engine started up, the horse bolted, and the cowboy was instantly dumped into the swamp! The three men were forced to walk to the Ruby Ranch, where they found a good steak dinner and another horse to pull them out of their fix.

Once the car had been pulled through the creek and up on to dry land, the men set out on the last 15 miles of the road that would bring them in to Wisdom. When they finally arrived in Wisdom they found that the anticipated celebration had worn off, and the steak dinner waiting there for them was cold and unused.

The celebrators themselves had finally given up on the two Bitter Rooters and were found just a little worse for wear in the town saloon where they had all gone afterwards to nurse their wounds and drown their sorrows. By the time the intrepid Darby motorists finally made a showing, Dick Hathaway, the editor of the ‘Big Hole Breezes’ was reportedly “filled to the gills with wild moose milk.” Sporting a huge 20-gallon hat, the jovial editor of the local paper quickly hoisted the two weary travelers up on to the bar top, where they were repeatedly toasted by the reinvigorated crowd, until everyone present was perfectly satisfied with the somewhat delayed outcome of the historic automotive adventure.

Early one fine September morning, after the damage to both the car and the drivers had been properly attended to, the men set forth on their return trip to the Bitter Root Valley. This time around they made it clear through to Darby in a single day, stopping once again for another hot steak dinner at the worker’s camp near the summit of Big Hole Mountain.

Eventually both Dr. Hayward and Al Rissman moved to Hamilton, where they each set up shop. Dr. Hayward continued to practice medicine, but Mr. Rissman got out of the drug store business and opened up a service station. Apparently he had lately come to realize that proper vehicle maintenance would soon be a necessary requirement for the traveler of the future.

For a while the Montana Highway Department took over the routine maintenance of the Big Hole Road, and guardrails were even installed on the sharp curves of the steep western slopes. Unfortunately, the guardrails were removed later on, and if you ever happen to be driving along the outside lane of the road, you’ll definitely appreciate how they might have helped to make a driver feel a little more confidant while rounding some of those narrow blind corners.

In 1963 a new road was opened up over Chief Joseph Pass, which connects the Big Hole Valley to Highway 93 near the Idaho state line. The U. S. Forest Service once again maintains the Gibbon’s Pass Road, and it’s likely that not too many people who cross over it these days are really aware of the story about the two local boys who drove the first car over the mountain.

No comments:

Post a Comment