This story is the first in a series about the Stevens Expedition

The 1850s were a time of great innovation and accomplishment, and in many ways the decade signaled the true opening of the American west.

The California gold rush was in full swing, and the Oregon Trail was flowing a steady stream of settlers to the rich Pacific Coast. In 1853 Congress divided the Oregon Territory in two, creating the Washington Territory. All of western Montana was encompassed in this new territory, along with the entire state of Idaho and parts of Wyoming.

Isaac Ingalls Stevens was selected as governor of the new territory, and his first order of business was to lead an expedition west, which would explore the possibility of building a northern route for a transcontinental railroad. The effort would launch the first real survey of this part of the country since the Lewis and Clark Expedition, nearly fifty years earlier.

Just like the Corps of Discovery, the Stevens Expedition was made up of both civilian and military personnel, which included civil engineers, surveyors, geologists, botanists, naturalists, meteorologists, astronomers, artists and physicians. Approximately 240 men in various detachments, set out from both coasts, most of them eventually converging at Saint Mary’s Village, near Fort Owen in the Bitterroot Valley.

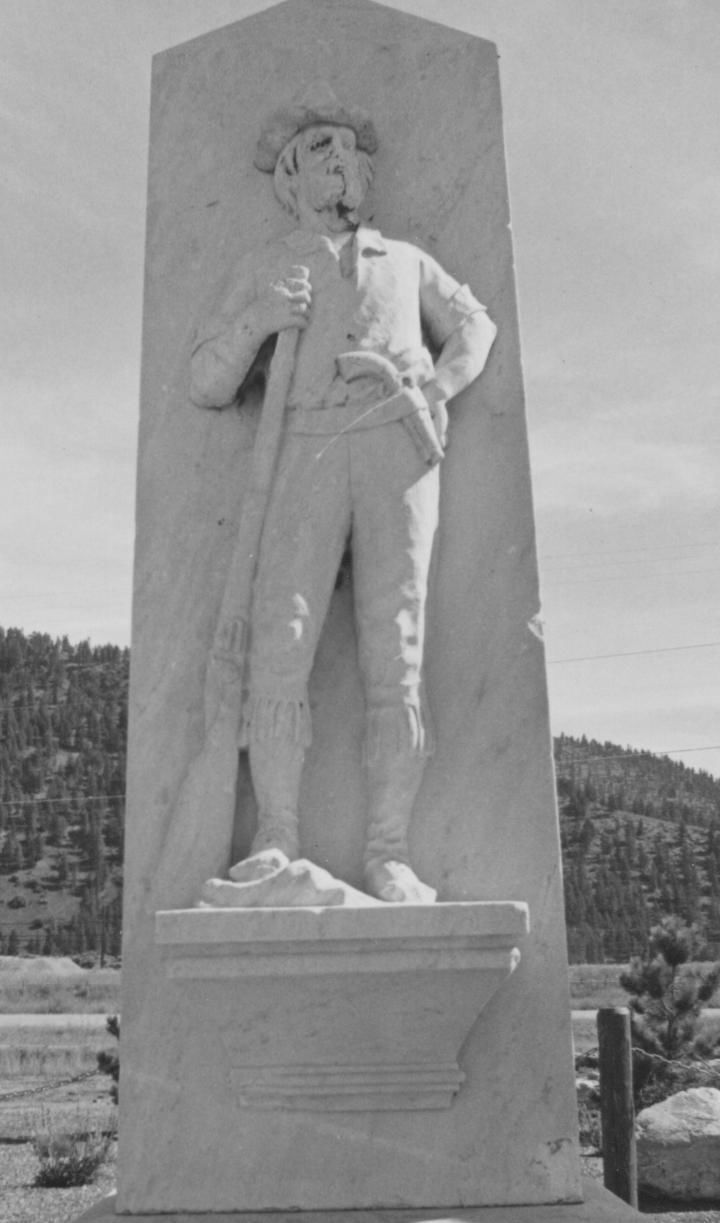

One member of the expedition who stood out from the others was a young officer by the name of John Mullan. The energetic Virginian had just graduated from West Point the year before, and was serving as a second Lieutenant stationed at Fort Columbus in New York, when he was selected to join the U.S. Pacific Rail Road Survey, under the direction of Governor Stevens.

While Stevens and the majority of the other members of the expedition started out crossing the plains with mules and wagons, Lieutenant Mullan and his small party caught a paddlewheel ship in St. Louis, owned and operated by the American Fur Company, and steamed up the Missouri to Fort Benton. Once there he received his written orders from the Governor to seek out a large band of Salish Indians who were hunting buffalo on the Musselshell River, and convince several of the chiefs to escort him to Fort Owen, where the governor would hold council with them.

Accompanying Mullan on this mission were three voyageurs, three Blackfeet Indians, and Mr. Rose, an interpreter for the fur company. Fred Burr, who had made the trip up the Missouri with Mullan, came along to make a barometric profile of the route. Both men would eventually take up quarters in the Bitterroot Valley at a military post called Cantonment Stevens, which was located approximately ten miles south of Fort Owen.

Lieutenant Mullan made several reconnaissance tours branching out from the Bitterroot, exploring passes east and west of the valley. He crossed the continental divide more often than any other member of the expedition, and successfully brought a wagonload of goods from Fort Benton to the Bitterroot, following a route similar to the one he had traveled initially with the Salish chiefs.

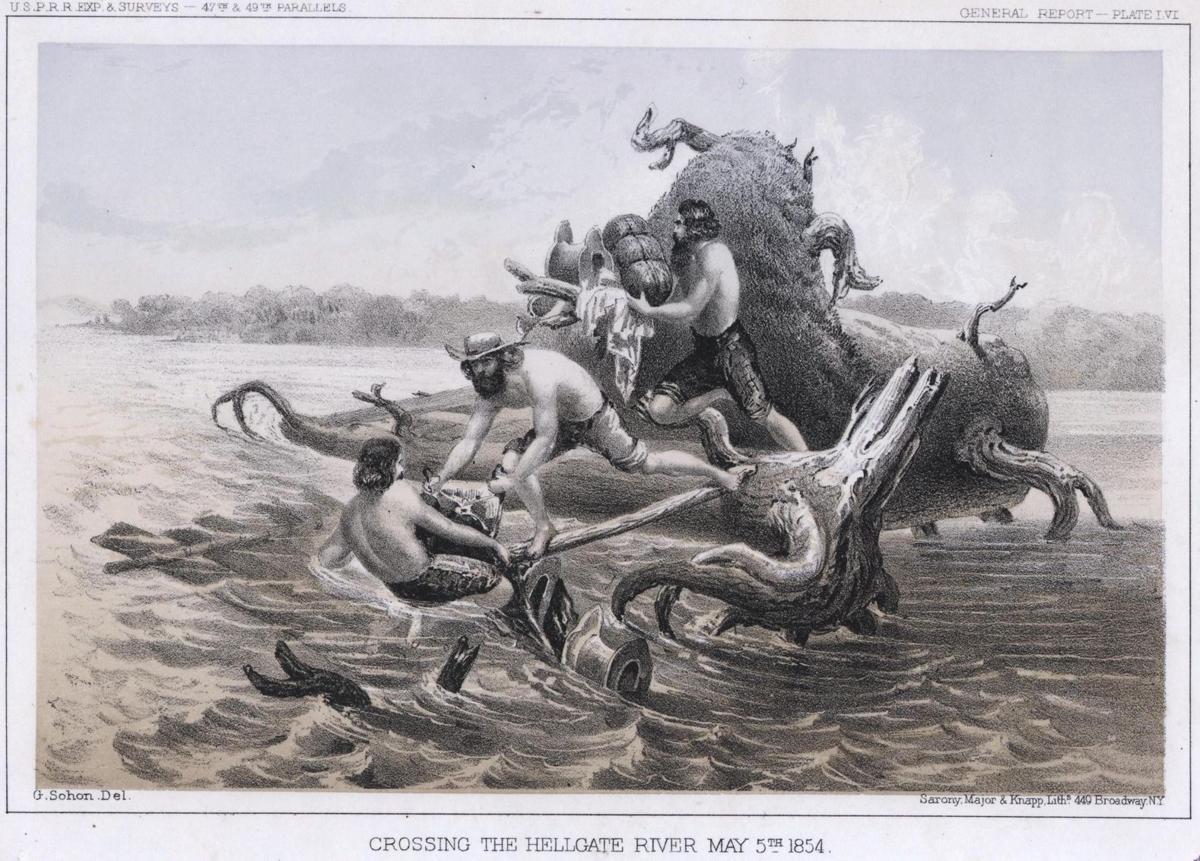

In the spring of 1854, Lieutenant Mullan explored the Flathead River up to Flathead Lake. He ventured up as far as the Kootenai River and on the return his party circled Flathead Lake and returned through the Jocko Valley and down Evaro Hill through the Coriacan Defile. At that time the Clark Fork was known as the Hell Gate River above the mouth of the Flathead, and when the party reached the river on May 4, 1854, near where Missoula is located today, they saw that the spring thaw had made the river too dangerous to cross on horseback.

In his journal Mullan reports that when they reached the river they “found it much swollen, deep, and very rapid. It here became necessary to build rafts, and setting the party at work, in three hours we made two rafts, and had everything ready for crossing. Gabriel, with one of the men, and an Indian woman and her children, were on one raft. Mr. Adams, myself, and my other remaining man were on the other raft. There was a point of land projecting from the opposite shore, which it was our intention to strike if possible. So impetuous was the current, that we moved in the channel with a headlong velocity, landing about a quarter of a mile down, on the same side from which we had started. Here so great was the current, that it was impossible to stop the raft, and we were thrown with frightful force against rocks, fallen trees, bushes, islands, in fact everything that formed an obstruction in the stream.”

“Half a mile from our point of starting, the current divided into two channels, carrying us to the opposite shore. Here we were brought up against a large fallen tree, the limbs of which we seized to stop the raft, but so strong was the current that we could not stem it for a moment, and moved with an awful swiftness down the stream. In our attempt to hold on by the limbs of the tree, I was knocked over board, compelling me to swim with my clothes. I succeeded in reaching the raft, with the aid of one of my men, who dragged me out of the water. At this place we lost our poles, and were thus left to the chances of fortune. We then stripped to facilitate our swimming, and on nearing a rocky island, each man with a line that had been made fast to the raft, sprang overboard, as a last resort to save the raft, and ourselves. By dint of perseverance and hard labor, we succeeded in holding it, allowing it to drift gradually against some fallen timber that lay at the end of the island.”

“To the left of this rocky island lay another island formed of fallen timber, but between the raft and the driftwood island lay a broad gulf of water, flowing with a most impetuous current. Here we had sufficient time to build a log bridge, and throw everything from the raft to the island. We succeeded in saving the greater portion of our property, but just as the last bale was removed from the raft, already two feet under water, the water dashed over it, and in a few minutes it was broken to pieces and carried down this much-dreaded river. Gabriel had been more successful, but had been compelled to swim with a cord three times, and with the aid of a horse, before he succeeded in landing safely. Here I am compelled to bear testimony to the great energy, courage, and activity displayed by Mr. Adams on an occasion when our whole party came near being drowned. Already fatigued by swimming, wading, and walking over rocks and stones, he threw everything from the raft to the island.”

“Here we were then, on a desolate island, naked, with a broad stream still between us and our shore of destination, and two miles from the point from whence we started. We fired our pistols to let the remainder of the party know that we were still alive, who having already become alarmed for our safety, had ridden many miles downstream in quest of us, but could not find us. Here Mr. Adams swam the stream, and naked and barefooted as he was, made his way through the bushes, briars, and fallen timber, to our camp, a mile distant. In two hours, with the aid of horses, we were relieved from our most unenviable situation, but succeeded in having everything that was saved, thoroughly wet. We rejoiced at finding the whole party thus saved from an untimely end, and with one accord were willing to remember the crossing of the Hell Gate River!”

After a year spent exploring the surrounding area, Lieutenant Mullan left Mr. Adams in charge as special Indian Agent to the Salish, and Fred Burr stayed behind as well. Conducting one final exploration, Mullan chose to continue his journey westward on the Old Lolo Trail, in the same month that Lewis and Clark had traveled it forty-nine years earlier! In 1858 Mullan was assigned the duty of constructing a military road from Fort Benton to Walla Walla.

The road was marked with the initials M.R. along the route, which stood for Military Road, but Mullan left such an indelible impression on those who worked alongside him and traveled the 624 mile-long road, that the M.R. was commonly thought to stand for Mullan Road. Portions of the original roadbed are still in use today, and have been integrated into our modern highway system. Some sections still carry the name of Mullan Road.

In 1862 Mullan was promoted to the rank of captain, and in 1865, after the completion of the military road, he wrote and published the ‘Miners and Travelers Guide to Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado via the Missouri and Columbia Rivers.’ He returned to Montana in 1883 with a group of dignitaries to witness the Last Spike Ceremony near Gold Creek, which signaled the completion of the Northern Pacific Rail Road, a full thirty years after he had first entered the state with the Stevens Expedition.

Remembering back to those early days in the rugged wide-open wilderness, Mullan reportedly said, “Night after night I have laid out in the unbeaten forests, or on the pathless prairies, with no bed but a few pine leaves, with no pillow but my saddle. In my imagination I heard the whistle of the engine, the whirr of machinery, the paddle of the steamboat wheels as they plowed the waters. In my enthusiasm I saw the country thickly populated, with thousands pouring over the borders to make homes in this far western land.” John Mullan was certainly one early Montana pioneer who made that dream a reality. Still, I can’t help but wonder how he would view the changes that have taken place since he first entered the vast and uncharted western wilderness.

No comments:

Post a Comment