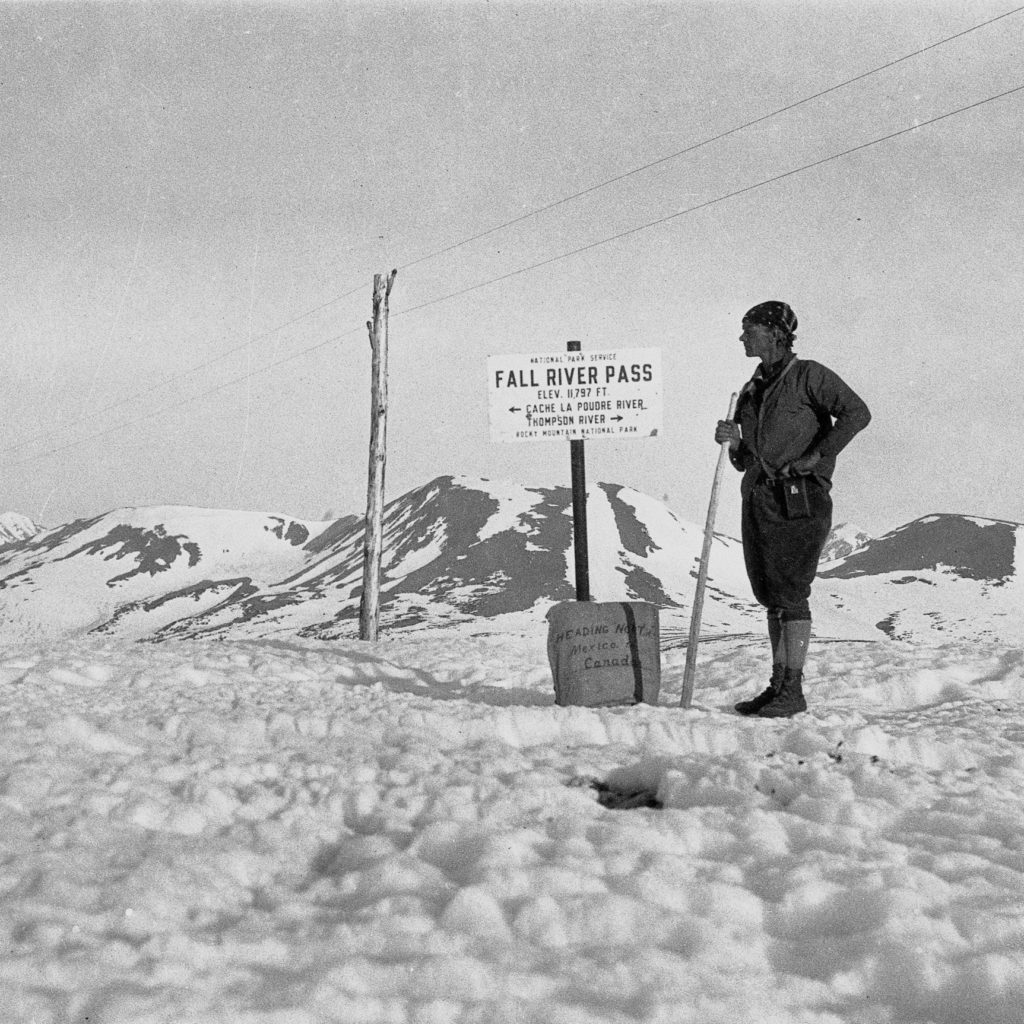

Parsons contemplates a snowy route ahead on his 1924 Divide transit. His 60-pound pack leans against the sign, announcing his intention in bold painted letters (right). Photo courtesy of Ursula Bassett.

This piece is an excerpt from our CDTC Board Member Barney Scout Mann’s book: The Continental Divide Trail: Exploring America’s Ridgeline Trail (Rizzoli, 2018).

Portions of proceeds from this book help support the Continental Divide Trail Coalition. See more of Mann’s work on his website.

His hands must have been freezing when he wrote in the summit register at 10,405 feet. It was 9:45 a.m., and he was all alone on Mount Jefferson in the Oregon Cascades. Tackling the difficult esat glacier route, he must have been exhausted after the long climb. Two weeks earlier, on Mount Rainier, he had only signed his name. What possessed him that day to run chatty?

On August 26, 1924, Peter Parsons left this register entry on an Oregon peak 400 miles off the Continental Divide: “Left Jefferson Park at 6:00 a.m. Arrived here at 9:45 a.m. Followed around the mountain over the glacier on the east side, then up a rock spur to the saddle… I believe this is a much more difficult route than from the southwest; but I will try to get down the same way. I started a hiking trip from the Mexican border April 12 and followed the Rocky Mountains north to Canada, then across to Mount Rainier; then south along the Cascades here. Four-and-a-half months on the way [Parson’s emphasis].”

Many claim the Divide was first hiked from Mexico to Canada in 1972 others claim it was in 1977. This register entry was the only evidence of Parson’s journey. Did he really do it in 1924?

Following a trail as faint as a cross-country route on the Divide led to the door of Ursula Bassett in Longview, Washington. Her father, Otto Witt, had jumped ship in Parsons in 1909. After all these years, Bassett still had Parson’s nearly century-old journals and two-by-three inch negatives in her basement. When magnified, one negative—Parsons at Colorado’s Fall River Pass—showed that in the summer of 1924, he had painted big block letters on his 60-pound canvas rucksack: “Heading North, Mexico to Canada.”

On April 12, 1924, with a gallon of water and cans of beans in his pack, Parsons hiked out of Douglas, Arizona, a border town just west of the Divide. Three days later, he rose out of the sparse ranchland and slogged through knee-deep snow at 8,000 feet. “There may be charms to the plains and the desert, but it’s the mountains for me,” he wrote in his journal. In air clear as polished glass, he experienced a common Divide phenomenon: “The mountains ahead look as far off as when I started.”

Born in Sweden in 1888, Parsons came to the United State in 1909. He jumped ship in Portland, Oregon, after the captain of the tall-mast schooner badly beat the cook. Well muscled and long armed, with deep-set blue eyes and thick brown hair, Parsons joined Witt and snuck down the gangplank. Two days laters and miles south, they were arrested as vagrants. AFter a night in jail, a judge pointed them to Hammond Lumber for work. That’s how Parsons and Witt came to live in Mill City, Oregon. For all of Parsons’s wanderlust, if anywhere was home, it was Mill City.

By day, Parsons and Witt worked in the lumber mill. By night, they devoured encyclopedias and books. Parsons often ramped in the Cascades, traveling cross-country and living off the land. He wintered two years in Alaska, running a line of animal traps. When he returned to Mill City from his latest adventure, he would work in the lumber mill, and then, once he’d built up a grubstake, go off exploring again.

In 1923, he tackled his longest trek yet. On foot from Detroit, Oregon, he hoped to reach Kernville, California, after 1,200 miles. Departing on June 23, Parsons came to Crater Lake on July 2. After passing Mount Shasta and Mount Lassen in Northern California, he reached Yosemite Valley on August 12 with only a half cup of beans in his pack. At Muir Pass, the scene was so different from today; the iconic domed Muir Hut wouldn’t be built for another decade. He reached Kernville on September 16.

After this successful trek, Parsons was ready to face the Continental Divide. His first postcard to his friend Witt was postmarked Silver City, New Mexico: “I am heading out cross-country.” To his journal, he confided it was going to be a “rough stretch.” The Gila River more than fulfilled the prophecy; it “zig-zagged from one side of the canyon to the other,” forcing him to cross it “almost every 100 feet.”

Midway through New Mexico, locals told him there was too much snow for him to get through. Time and again he heard doomsday predictions: “You can’t do it.” “Impossible.” Parsons decided to try anyway. Two days later, with that stretch done, his neat penmanship recorded, “I made 23 miles and the same yesterday.” In Chama, New Mexico, the state’s north end, he wrote, “Everybody said I could not get through because of the snow.” But Parsons did.

Early in Colorado, he made camp in six-foot drifts, but to Parsons it felt like familiar country. “It will freeze pretty hard I expect … This is like camping in Alaska.,” he wrote, and later that same night, in his bedroll. “I don’t know where I am at but it doesn’t matter.” Parsons was on the Great Divide.

Trails were few and the Colorado high country was riddled with old mines and cow camps. At small mercantile stores every three or four days, Parsons refilled his stock of beans, rice, and oats. He supplemented the spartan fare with wild game. But Parsons reached for his camera just as often as his gun. And the frontiersman had a tender spot. “I saw a grouse this afternoon but she had some chicks so I left her alone,” he wrote. “But she would have gone fine with my beans tonight.”

Unlike his friend Witt, Parsons was single. When cleaned up, the broad-shouldered 36-year-old was dashing. But while quick on the draw with a camera or a gun, he was the opposite socially. Wistfully, he wrote about meeting a woman outside Yellowstone: “While I was there a young lady came along driving a motorcycle. She was wearing boots, a slicker coat and the rain had beat her face till she was all flushed. I had a chat with her after I finished my coffee. She had been driving all the way from Philadelphia. She was the most self-sufficient young woman I had seen in a long time, she was one in a thousand [Parsons’s emphasis] … and I have been kicking myself for a silly ass ever since for not getting her name or address.”

And that left Witt as Parsons’s only correspondent. On penny postcards, Parsons updated his old shipmate on his journey: “I just came down from crossing 3 passes on the Continental Divide where the snow was 20 feet.” “I had to raft across a river.” “I did not see anybody for five days.” The rugged mountain man didn’t directly say it, but he must have been lonely. One postcard ended, “Get busy and send me a letter.”

In a Wyoming town, he bought a copy of Outdoor Life magazine. In his journal, he nonchalantly mentioned, “I found a brief description and a few photos of last year’s trip.” The popular magazine had given a full page to Parsons’s 1923 Oregon-to-California trek, including six photos.

By Montana, the snow had finally receded. It seemed to storm every day, which exposed a hole in the Swede’s impeccable English. Consistently, Parsons wrote “tunder” and “tunderstorms” in his journal. As he neared Glacier national Park, Canada was in his sights and hints of giddiness leaked into his penciled lines: “I walked barefoot for several miles this pm, the trail as soft as velvet underfoot from half decayed tree mold, needles and moss.” A lake was “the deepest blue with ice cakes floating on it.” And even when the expert navigator was rudely surprised—at one point, he realized he was on the wrong river—he pranced naked instead of brooding: “Tonight I have been running around here stark nude a couple of hours.”

Swiftcurrent Pass was windy, exposed, and high. But none of that mattered to Parsons. One last time he wanted to camp on the Divide. Four days later, on July 14, 1924, the crazy hope Parsons had painted on his pack—Mexico to Canada—became fact. Parsons leaned that rucksack against the bare metal of the border monument, stuck his fist in the air, and snapped a photo. It’s a safe bet that Parsons let out a yell. At 2:00 p.m., he crossed the border into Canada.”

No comments:

Post a Comment