Lead photograph courtesy of Tucker Sno-Cat Archives.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Overland Journal’s Winter 2022 Issue.

After decades of deliberation, I bought a snowcat a couple of years ago—a Kristi, manufactured in Denver about 1963. Powered by a 36-horsepower VW air-cooled motor, it had sat idle outdoors for over a decade.

Perhaps the idea was seeded in boyhood when I read about the International Geophysics Year of 1957-58, a period devoted to intense study of the planet Earth: geomagnetism, seismology, volcanology, and more precise mapping of the few remaining unknown corners of our planet, principally the Antarctic Continent.

The period initiated a Golden Age of motorized over-the-snow travel with the frozen crucibles of the North and South Poles as testing fields.

By the early 20th century, a growing rural road network in the US and Canada called for transportation to negotiate wintry conditions. Snowplowing was uncommon before World War II, and many farms, ranches, and small communities remained seasonally isolated. By the late 1930s, a telephone network and the rural electrification program were well underway. Oil and gas exploration was moving to more remote northerly regions. Commercial and governmental interests had powerful incentives to access and provide services in winter.

Early Efforts

The automotive, aircraft, agriculture, and military sectors all influenced the early development of the over-the-snow industry. While commerce remained the focus, that unique human desire to play in the snow in novel ways was not overlooked.

The fits-and-starts efforts of backyard mechanics and small-time innovators proved particularly influential in the post-Depression years. Track-and-ski kits, for example, were often fitted to cars and trucks, with decidedly mixed results. Some experimented with units powered by large rear-mounted wooden propellers. These aircraft-inspired “snowplanes” were used to deliver mail in some of the broad valleys and prairies of the West. Speeds approaching 100 mph could be attained over proper terrain, but snowplanes were generally limited to a single pilot and limited cargo.

Snowplanes, such as this shop-built Alberta example from 1935, were sometimes used to deliver mail. Photo courtesy of Provincial Archives of Alberta.

The largely self-taught Joseph-Armand Bombardier of Valcourt, Quebec, took out several patents by 1937 for over-the-snow machines. His company would go on to build highly successful models of snowcoaches designed to carry passengers and cargo over existing snow-packed roadways. Bombardier snowcoaches became iconic wintertime transportation in Yellowstone National Park over many decades.

In the late 1940s, Bombardier began production of an innovative steel track system that could be retrofitted to standard agricultural tractors for heavy work in winter. Known as the Tracking Tractor Attachment, the design would be licensed and sold in various forms throughout the Western Hemisphere and Europe. This and other Bombardier designs would make a lasting mark on winter transportation and the history of polar exploration.

A 12-passenger Bombardier B12, leaving the Valcourt, Quebec, factory in 1941. Photocourtesy of Bombardier Archives.

The Sno-Cat is Born

In the US, Emmitt M. Tucker was done experimenting with machines powered by two spiral-drive pontoons designed to float over the snow while moving along in a corkscrew fashion. The pontoon idea stayed with the inventor, though, and by 1938, he had applied continuous steel track, which offered flotation and traction. Based out of Medford, Oregon, since 1947, Tucker Sno-Cat Corporation built a reputation for hardy, powerful machines that won military contracts during and following WWII, including for base establishment in Antarctica.

Tucker eventually came out with models that featured four tracked pontoons that could be steered both front and rear, greatly improving mobility. “No snow too deep, no road too steep” became the company’s motto, and its success attracted wider attention.

This screw-propelled Fordson tractor was put to work in Yellowstone National Park near Cooke City in the early 1920s.

Expedition Ready

By the early 1950s, a British Commonwealth scientific expedition was well into the planning phases with a goal to motor across Antarctica. Chief transport engineer David Pratt was charged with logistics and machine procurement. His criteria included the following.

- Spark-combustion gasoline engines (diesel, gels at low temperatures)

- Cold-start capabilities at -40°F, pre-heated cold-start at -60°F

- Ability to negotiate highly variable terrain and crevasses while towing up to 4 tons

- Average 20 miles per day at 1.41 mpg, minimum

Pratt selected and arranged the purchase and delivery of four customized Model 743 Tucker Sno-Cats for the proposed 2,100-mile first crossing of Antarctica. Each factory-customized unit came in at 3.5 tons, powered by a 331 Chrysler Hemi V-8, delivering about 180 horsepower.

Eleven countries took part in Antarctic activities of the Geophysics Year. The US supported and augmented the overland scientific expedition crossing the South Pole, under the command of geologist and explorer Sir Vivian Fuchs, with David Pratt as chief engineer.

Three gentlemen sit astride an E.M. Tucker personal snow machine prototype in 1945. Photo courtesy of Tucker Sno-Cat Archives.

Fuchs organized the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1955-58 as a private venture, with assistance from various governments. The US Navy supported the establishment of bases and depots, both by ship and air. While nominally independent of the Geophysics Year, Fuchs agreed to work closely on scientific aspects, such as seismic mapping of the Antarctic Plateau.

Having bagged Mount Everest in 1953, New Zealander Sir Edmund Hillary seemed a natural choice to share leadership of the expedition. Fuchs must have been thrilled when the internationally famous climber and explorer agreed to sign on. Hillary’s job was to first establish a base near the US facility at McMurdo Sound on the Ross Sea side of the Antarctic. Then, using dog sleds with air reconnaissance and supply, his light team would plot half the route toward the South Pole.

The plan was for a series of fuel and supply depots to be in place for the heavy Tucker-supported Fuchs team coming in from Camp Shackleton on the Weddell Sea side of the continent.

Hillary had seen track-equipped tractors hauling logs in Norway and became convinced the Bombardier-designed system could be adapted to polar motorized transport. Lacking the generous funding of the Fuchs team, Hillary asked the Ferguson Tractor Company to loan four TE20 units (tractor, English-built, 20 horsepower) for the Kiwi effort.

Hillary’s team modified the Ferguson tractors on-site at Scott Base, including an extra low-end transfer case. According to a post-expedition engineering report by David Pratt, that additional 4.5 inches in length was critical for negotiating crevasses.

The most notable modification was the installation of Bombardier-designed continuous cleated steel tracks over the front and rear wheels with alignment “bogie wheels” in between.

In testing the tractors, Hillary was convinced the vehicles could go beyond merely establishing supply depots. After installing the forward-most Depot 700 (the number of miles from Camp Scott), Hillary drove one of the three Fergusons Photo 007, 008 on a dash to the South Pole 16 days ahead of the Tucker-supported British Fuchs team. The diminutive “Fergies” became the first motorized overland vehicles to reach the South Pole on January 4, 1958. Perhaps fittingly, each was driven by a New Zealander, fueled at times and assisted by US Navy gasoline and aircraft, and equipped with Canadian-designed tracks.

The Tucker-supported Fuchs team attained the Pole and followed Hillary’s route, reaching Scott Base after 99 days of travel over ice and snow, effectively completing a transect of the continent.

Fuchs confirmed the South Pole is roughly 9,000 feet of ice sheet over a low-lying land mass and was awarded knighthood upon return to England. Sir Edmund Hillary’s likeness still appears on the New Zealand five-dollar note, for many years, alongside a miniature image of a Ferguson tractor. The international cooperative Antarctic Treaty was signed in 1959.

Upon recommendation by members of the Commonwealth expedition, a point off the Ross Sea was named “Mount Tucker.”

Ski-Doo’s New Era

Over-the-snow innovation and exploration didn’t end with the Geophysics Year. By 1959, J.A. Bombardier was again refining the company’s sprocket, continuous track, and suspension systems, this time with an eye toward personal recreation. Bombardier introduced the Ski-Doo snow machine in 1959, selling a handful that first year. Ten years later, sales would approach 100,000. The soundscape of the North American winter would be changed forever.

Ski-Doo wasn’t the first snow machine, but by the late 1960s, the bumblebee yellow and black color scheme came to dominate a crowded manufacturing field. Conspicuously absent was the Tucker Sno-Cat. Emmitt Tucker applied for and received a US patent in 1945 and built at least one snowmobile prototype. Oddly, the company never went into production with a single personal snowmobile model.

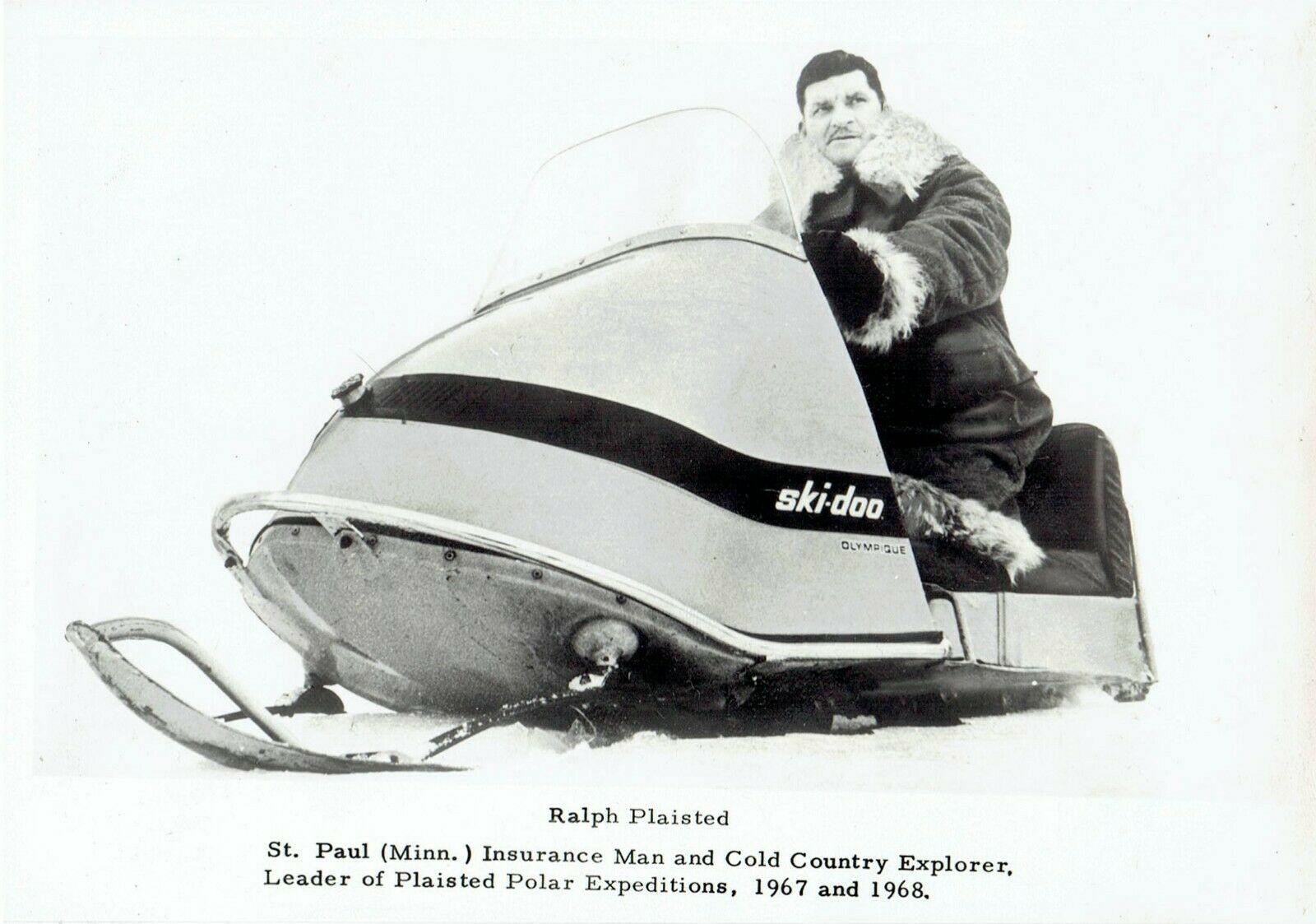

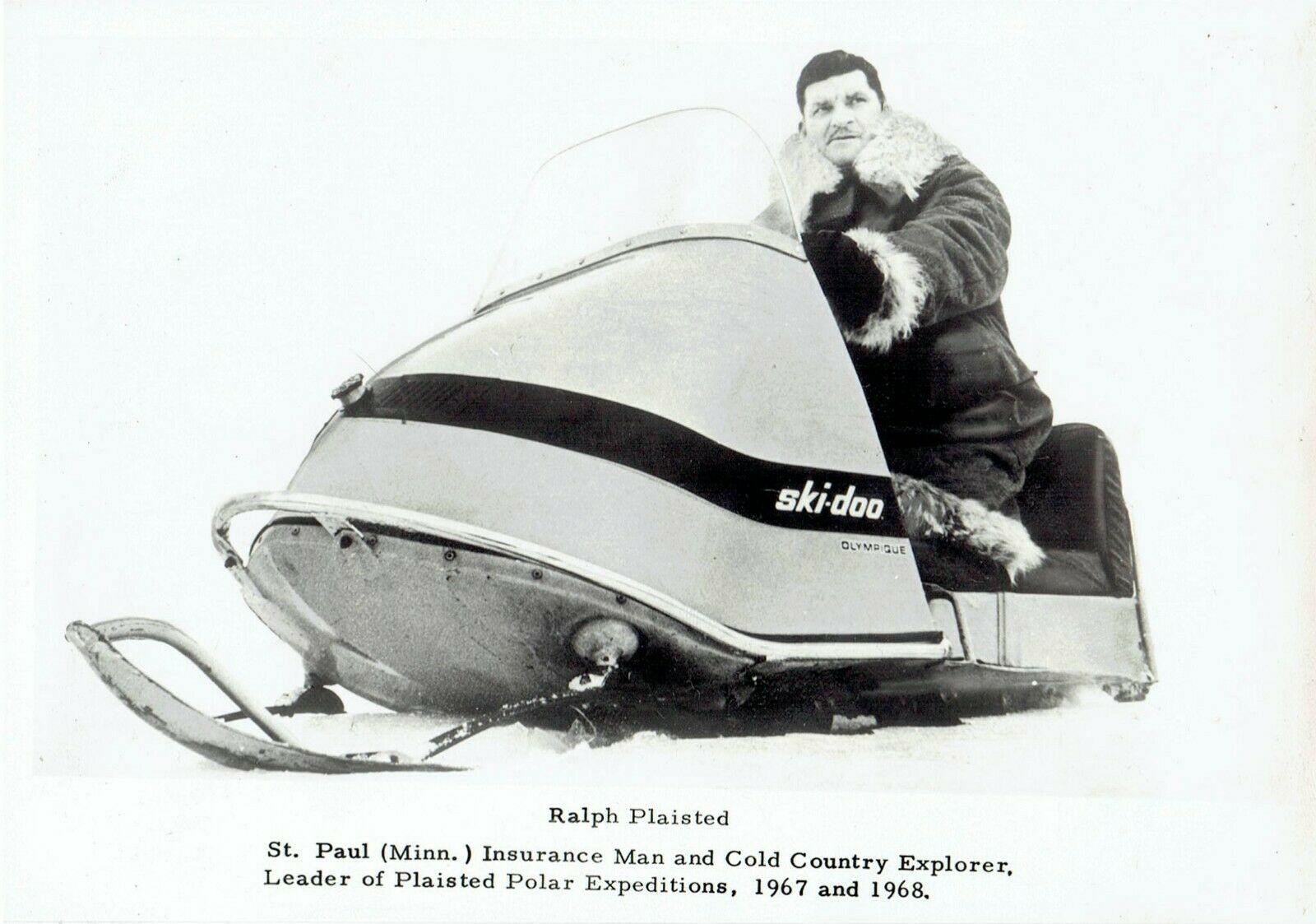

Ralph Plaisted, a Minnesota insurance salesman, was so impressed by the capabilities of the Bombardier Ski-Doo that in the mid-1960s, he initiated plans to ride snowmobiles to the North Pole. The company provided eight machines with the proviso that 28-year-old Jean-Luc Bombardier—a notable racer and nephew to the founder—be a part of the team.

This Sno-Cat from the Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1955-58 today resides in a museum in Christchurch, New Zealand. Photo courtesy of Tucker Sno-Cat Archives.

The 1968 Ski-Doo “Super” Olympique weighed about 380 pounds and produced 16 horsepower out of its 300cc two-stroke motor. Each unit carried two riders during the initial phases while towing a gear-laden sled. The team mechanic made several key modifications, including an extra fuel tank and golf shoe cleats mounted all over the single rubber track.

Minnesota sponsors provided the best in clothing, gear, and prepared foods. Plaisted enlisted air support out of Ellesmere Island for reconnaissance and to drop fuel and supplies, which reportedly included beer, cigarettes, and scotch whisky.

Since the North Pole is an icecap over seawater, Plaisted had to launch in February while ice conditions were relatively stable. In the bitter cold mornings, the team mechanic would soak a rag in fuel, hang it off a wire in front of the machine’s air intake, and light it on fire while working the pull start. Riders traveled back and forth from previous depots to ferry supplies as the team inched toward the Pole.

Three team members, riding singly to improve speed, accompanied Plaisted on the final push to the Pole. On April 19, 1968, the navigator reckoned the Pole had been attained. A US Air Force jet pilot on weather patrol made radio contact with the team and confirmed the position. The men camped overnight at the Pole and started back along the same route where a supply plane picked them up several days later. The team was on the ice for 45 days. Because of detours around pressure ridges and open water, the 450-mile assault tallied closer to 850.

World events that spring overshadowed publicity of the achievement. Twenty years later, the National Geographic Society would begin its famous retraction of its longstanding endorsement of Commander Robert Peary’s 1909 claim as the first person to reach the North Pole. The New York Times, which co-sponsored Peary, issued a rare correction in 1989.

The 1968 Ralph Plaisted Ski-Doo snowmobile expedition remains the first and only confirmed motorized over-the-ice effort to reach the North Pole. Open water conditions today make the feat almost impossible to repeat.

Sir Edmund Hillary, aboard his Ferguson TE20 in Antarctica, circa 1957. Photo courtesy of New Zealand TAE Archives.

Personal Snow Machines

Sales of recreational snowmobiles peaked in the early 1970s, although more powerful models remain popular. Today, the US Forest Service, National Parks Service, and other federal agencies carefully control motorized over-the-snow vehicles, wishing to balance a range of backcountry uses while protecting wildlife and the soundscape of a formerly quiet winter. Regulations among the national forests vary considerably.

Bombardier long ago spun off its over-the-snow business, concentrating on public rail and aircraft manufacturing. However, Ski-Doo remains in Canadian production and is a respected marque among winter riders. Reportedly, more than three million Ski-Doo snowmobiles have been sold since 1959.

Snowcat Evolution

The snowcat industry would further evolve to mainly serve traditional commercial and industrial interests. By the early 1970s, snowcats had found a new purpose in the grooming of corduroy ski runs at lift-supported resorts as well as snowmobile trails on National Forest lands. Nonetheless, snowcat manufacturing in North America has foundered with well-known and obscure brands ending production.

Still, private recreational use of snowcats has grown in recent years, usually restored commercial models, many of which are brought out of retirement, retrofitted, and insulated for onboard overnight accommodations.

Those bright orange Tucker Sno-Cats remain a part of the winter landscape, and the family-owned company stands alone among North American manufacturers, serving a niche commercial market. Tucker still makes its trademark four-pontoon design, although rubber track units are also available. Further, the company offers a restoration service of even the most antique units, including the big Model 743s that helped open up the globe’s last frontier.

New Zealand dropped the tiny Ferguson tractor image from its Sir Edmund Hillary five-dollar bill in 2016 to make room for a security code.

By all accounts, Mount Tucker in Antarctica remains standing.

Snow machines were commonly seen lending a hand on ski slopes.

Timeline

1922-26: Canadians Karl Lorch and J.M. Bombardier develop early propeller-driven snowplanes. In the US, E.M. Tucker and others develop screw-propelled machines.

1926: A screw-propelled tractor is used to support Detroit Wilkes Aviation Expedition. It fails in deep snow outside of Nenana, Alaska.

1936-37: Bombardier develops rubber-encased sprockets and innovative tracks. The company produces its first snowcoach, holding eight passengers.

1939-40: A 33.5-ton, 55-foot long, US-built “snow cruiser” is brought to Antarctica. The rubber-wheeled unit contains living quarters with fuel and supplies for one year. It fails almost immediately and today is believed to be lost in the Ross Ice Shelf.

1940-45: US and Canada militaries purchase metal track, sprocket-driven “Weasels,” powered by Studebaker motors and used to support the legendary 10th Mountain Division. The US lets contracts with Tucker, while Canada turns to Bombardier for heavy over-the-snow units.

1946: Inventor Harry Ferguson introduces the TE20 tractor, which Sir Edmund Hillary and mechanic Jim Bates modify for the first mechanized expedition to the South Pole.

1947: The Frandee snowcat was developed by Utah Scientific Foundation, associated with what becomes Utah State University in Logan.

1950-52: The first US Soil Conservation Service Snowcat Trials are held in Sun Valley. Steve Bradley at Winter Park, Colorado, patents the first ski run groomer, originally towed by Tucker Sno-Cats and later by Kristi and Thiokol at various resorts.

1953: Bombardier unveils the Muskeg, used primarily for northern oil exploration. Bruce Nodwell of Calgary introduces a similar heavy unit to carry seismic drilling equipment.

Minnesota insurance man Ralph Plaisted proudly perches on a Ski-Doo “Super” Olympique snow machine. His team rode three of them to the North Pole in 1968. Expedition press release photo.

1956: Utah Scientific develops the large Trackmaster with a transmission for each track, powered by rubber-coated sprockets.

1958: J.A. Bombardier builds prototypes for a personal snow machine named the Ski-Dog. A later misprint labels the machine Ski-Doo. The rest is history.

Late 1950s: Kristi of Denver pivots from building snowplanes to making fiberglass-body snowcats powered by air-cooled VW engines with unique hydraulically operated leveling. The company ceases production in 1972.

Early 1960s: Utah Scientific turns over production to Thiokol, which becomes DMC, owned by carmaker John DeLorean, and eventually Logan Manufacturing. Production ends in the year 2000.

1969-70: Ski resort snow grooming grows as Thiokol introduces the Packmaster with 5-foot wide tracks. Using Bradley’s design, it clears moguls while grooming ski runs and trails.

2016: After almost 60 years of service, Yellowstone Park auctions off its line of Bombardier snowcoaches.

Our No Compromise Clause: We carefully screen all contributors to ensure they are independent and impartial. We never have and never will accept advertorial, and we do not allow advertising to influence our product or destination reviews.

Read more: How to Prepare for an Overland Journey in the Depth of Winter