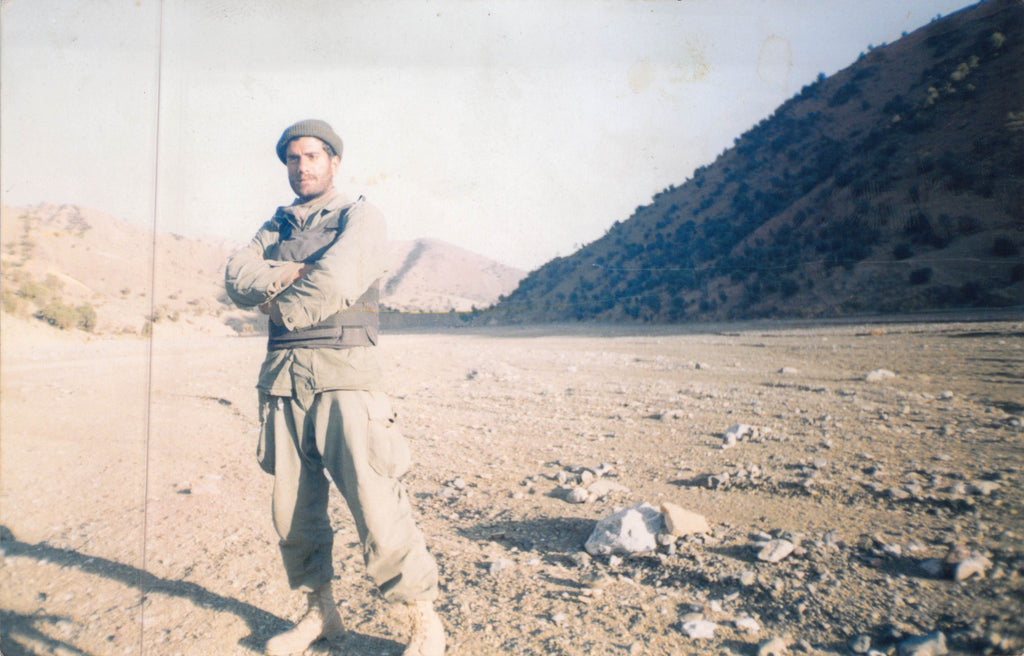

More than 20,” he said, delivering the statement as a matter of fact, devoid of emotion. That’s not to say Mohammad Wali Tasleem — a ruggedly handsome, middle-aged Afghan man with long black hair and a square jaw — didn’t mourn the death of his family members. Rather, it’s the by-product of a hard man who was born into violence and, until recently, had continued to live a life intimately intertwined with the same.

In Wali’s case, a much more violent life than even his fellow Afghans.

He continued on, narrating a long list of close family members who fell to the Soviet Army during their failed invasion of Afghanistan in the 1980s, as well as the Taliban afterward.

“Two of my brothers. My sister. My uncle. My cousin. One of my brothers, he lost his leg. One other cousin got shot.”

It’s an appalling amount of death in one family, and certainly a lot for a child to deal with. Or so we would think, here in America.

But life in Afghanistan was, and is, different. A familiarity with death and violence is bred into Afghans at a young age. Indeed, Wali’s friends would find antipersonnel landmines buried by the Soviets near their village and use them to go fishing.

“They didn’t know. They didn’t have information about that,” he said. Many would pay for their childish curiosity with their lives.

Wali’s older family members fought in the Mujahedeen, which resulted in threats to their life from the Soviets. His dad, a former chief of education in Afghanistan, had to hide in a tree all night during the dead of winter to avoid capture on one occasion. At some point it all became too dangerous, so Wali’s family fled to Pakistan.

“We had some good time[s] in Pakistan,” he recalled, “because I was 7 years old and had no responsibility. Just playing with the kids and school.”

Despite the chaos of his youth, Wali knew what he wanted to be when he grew up: “My goal was to be a good Afghan Commando.” His brothers would return from fighting in Afghanistan and tell tales of daring Commandos; after Wali returned to Afghanistan, he saw some of them for himself. He’s not unlike many special operators currently serving in the American military, many of whom grew up wanting to be Green Berets, Army Rangers, or Navy SEALs.

When I heard about 9/11, I was in Iran,” Wali recalled. The pressure from the Taliban and Al-Qaeda had become too much, so they had to flee once again. But Wali was older at that point and not happy about the attacks on America. “It was not just bad news for me, but for the human. The human is not for killing,” he said.

Unwittingly following the same path as many of his American peers in the aftermath of 9/11, he joined the Afghan Army at the age of 17. He received training in marksmanship, close-quarters battle (CQB), ambushes, reacting to contact, and breaking contact. The training was very similar to what US soldiers learned during their own basic training. The difference, unlike many soldiers, is that Wali would go straight to the frontlines in his own country afterward.

It wouldn’t be long until Wali was working with American advisors, who were most likely US Army Special Forces soldiers at that time. He went on to work with more than 500 American advisors over the course of his 13-year career and had a very positive experience with them. A few stuck out though: Jeff Kirkham, Evan Hafer, and Dale Comstock.

“They were the best,” he said, a smile on his face. Although the competence and experience of American Special Forces soldiers certainly helped in the early days of America’s forever war, the effort would have been for naught had it not been for exceptional men like Wali in the Afghan military’s ranks.

His goal was to eventually become a commander, a position he was bound to achieve given his background as a boxing champion, command of the English language, and extraordinary knack for leading soldiers. In a land where corruption runs rampant, it didn’t hurt that Wali was also an honest man willing to work hard.

Dale Comstock, a career special operations soldier who was one of Wali’s advisors, said, “Everyone followed and respected him.” Comstock and Wali worked together for years, going on hundreds of operations together. “I could go out on the range with him and his platoon, [and] train them on basic pistol marksmanship. A month later he would go out and teach the same class to a T,” Comstock said, explaining that it didn’t matter what he was teaching, Wali was able to turn around and teach them just as well as he did. “And we did a lot of ... very advanced stuff.”

On the surface, it may seem that Wali was a naturally gifted soldier, someone who just got it when it came to military tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs). Although that may have been the case, one shouldn’t assume that his talents didn’t require an enormous amount of work that largely went unrecognized. Just like a pro athlete who works his ass off in practice, he put in more work than his Afghan peers, hoping to rise to the next level.

“He showed me this little notebook he always took to the range,” Comstock said, his voice projecting a mix of excitement and adoration as he described the day he discovered how much work Wali was actually putting into the job. After the day’s training was over, “he would copy [his notes] into a big notebook in his room, complete with diagrams and everything.” Wali studied religiously; the devotion to his craft was evident in the more than 1,500 combat missions he conducted over the course of his career.

The Khyber Pass is a historically significant piece of geography that connects Afghanistan and Pakistan. (Rudyard Kipling once called the pass “a sword that cuts through the mountain.”) More specifically, the Spin Ghar mountains in present-day Nuristan Province, which is an area as vital today to military strategists, drug smugglers, and black market gun runners as it was to Genghis Khan and his ilk back in the 13th century.

It’s the Wild West — or, in Afghanistan’s case, the wild east — and would be the area that Wali, Comstock, and their crack unit of Commandos would find themselves headed to on a mission in support of a US Naval special operations unit. At the time, the violence in Afghanistan was at a peak. US casualties were at an all-time high, and the danger to both coalition soldiers and Afghans was very real.

The mission was to rescue an American and his interpreter that had been left behind after the Naval unit was picked up after a mission, Comstock said. They were stranded in a truck, sitting in the middle of nowhere, hoping someone — anyone — would come get them before the bad guys figured out that they were there.

Wali’s Commandos, along with Comstock as the sole American advisor, were called up to conduct the extraction. They loaded a Chinook helicopter and lifted off, racing through the night air to get to the stranded duo in time. The twin rotors churned through the air while the airframe vibrated aggressively as the combat-hardened Commandos put their game faces on. Unlike many missions where the objective was to find and kill someone, this circumstance presented the rare opportunity to savetwo people.

The bird flared and lowered to the ground, causing a brown out and momentarily masking the Commandos as they ran off the back ramp to establish a security perimeter. The helicopter lifted back off again, and the Afghans rose from their knees and pushed out to where the truck was.

“These guys (Commandos) were real pipe hitters; they took the business of warfighting very seriously,” Comstock recalled.

It didn’t take long to reach them, and thankfully both the ‘terp and the American were okay when they arrived. Unfortunately for the entire group, headlights started bouncing up and down in the distance. Multiple trucks loaded with insurgents armed to the teeth were speeding toward them, and the impending encounter was not likely to be friendly.

The trucks surrounded their position, and they braced for the inevitable firefight. What Wali did next quite possibly saved everyone’s life that night, according to Comstock.

“Wali runs down the hill to yell at them, ‘Hey, we’re Afghans, we’re here to liberate Afghanistan!’” Wali proceeded to completely de-escalate the situation. “He broke bread, said he’s one of them,” Comstock recalled, “and he talked his way out of it.”

They ended up towing the truck out and driving 18 hours back to Kabul. It wasn’t the first time that Wali had pulled such a stunt though. Comstock said they would regularly do long convoy movements in “jingle trucks” to get to a target. It was common to run into Taliban checkpoints or be stopped by corrupt Afghan National Army (ANA) soldiers. Wali, always as charming as he needed to be, was able to talk his way through the checkpoints every time. “These guys (Commandos) were real pipe hitters; they took the business of warfighting very seriously,” Comstock recalled. “Wali thought outside the box, he was very good.”

As the years went by, the Taliban put more and more pressure on Wali and his family. They received phone calls threatening to kill his wife and kids with disturbing regularity. Then the assassination attempts started. “Five times,” Wali responded when asked how many attempts there were on his life. Two of those instances involved his house being surrounded; another resulted in his car being riddled with over 19 bullet holes.

Starting in 2009 and acting on the advice of his American advisors, Wali and his family started moving every three to six months, trying to stay out of the crosshairs of the Taliban. All the while, his family thought he was just working for the government. “I kept it a secret … that I was a Commando, from my family.” If that didn’t create enough stress, he was also gone for weeks or months at a time conducting missions all over Afghanistan.

He had grown close with his advisors, but at some point all deployments must come to an end for Americans in Afghanistan. Such was the case for Comstock, who never quit thinking about Wali after he returned home.

“I felt like he was my son,” he said. “I thought, ‘Man, when this war is over, he’s gonna be fucked.’ I always worried about that.”

Special Forces veteran Jeff Kirkham, one of Wali’s other American advisors, had even heard that Wali was killed in action at one point.

With the life expectancy in Afghanistan far below that of Western nations, it was a legitimate fear. In fact, over 50 percent of Afghans are under the age of 19. Wali was obviously aware of this, and given the nature of his job and the mounting threats and assassination attempts, he decided change was necessary.

In 2013, Wali came to his American advisors to tell them that he would like their help in moving him and his family to America “to help keep safe my kids and wife.” Many Afghans who have worked with the US military have found the process to acquire a Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) daunting in even the best scenarios. Some wait years to finally be accepted, others are still waiting to this day.

Wali was not like most applicants though; he was an Afghan special operations commander, spoke five languages, and had proven his trustworthiness on multiple occasions. He had certificates from American senators, recommendations from four-star generals, as well as the strong referrals from his elite advisors who worked with him every day.

Finally, two years later in 2015, Mohammad Wali Tasleem received his SIV. His wife and five sons each packed a bag — seven bags for seven people — and boarded a flight to America to start their new life.

The Tasleem family landed in Newark, New Jersey, and stepped off the plane onto American soil for the first time. Wali couldn’t help but smile when describing the feelings that washed over him: “We will be safe here, my kids will go to a good school, and they will grow up in a good country.” After a one-night stay at a hotel in Newark, they completed the last leg of their journey and arrived at their new home in Charlottesville, Virginia.

At first, finding work as a security guard wasn’t hard, and Wali and his wife had help acquiring a house and getting the kids into school. But all was not well. The other parents in the neighborhood wouldn’t let their kids play with Wali’s, and he eventually had to take a job as a gas station cashier after the three months of security work ended. Before long, they had to move into public housing where the neighbors always seemed to be drunk and confrontational.

“I had a hard life in public housing,” Wali said. “In Afghanistan, I was a Commando. In America, I was a cashier.”

As the sole income earner for his family of seven, paying bills and providing for his household was a challenge. It seemed as if one set of problems had been traded in for another.

One night, after work, I turned on [the] TV and I saw one of my best friends, Mr. Jeff,” Wali said, referring to his former advisor Jeff Kirkham.

They had worked together on and off for almost 12 years in Afghanistan, and Wali wanted to get in touch. So, he took to social media. “I looked up his personal Facebook and sent him a friend request.” He asked Jeff if he remembered him, and of course Jeff did. They caught up over the phone, and Jeff was distraught to hear that Wali was working at a gas station.

Jeff talked to his friend and business partner, Black Rifle Coffee Company’s CEO Evan Hafer, about the situation. A week later, Wali was in Salt Lake City taking a tour of the BRCC facility. It wasn’t just a tour though: Evan and Jeff were prepared with a job offer.

Wali accepted the job, which entailed working in the BRCC print shop, and moved his entire family to Utah. A fully furnished house was waiting for him, courtesy of his new employers. He no longer had to worry about the violence inherent in his past life, constant threats, or a lack of opportunity for his family. The Tasleem family, a clan that had endured more than most people can imagine, finally felt at home in America.

He now shows up to work every day with a smile on his face. He’s amongst like-minded individuals at work, many of whom also served and sacrificed in Afghanistan. He prints thousands of shirts a day and considers BRCC his second home.

For a man who should have died many times over, who was born into a dystopian landscape fraught with decades of war and suffering, Wali should not — logically — be living a quiet, happy suburban life with his family. Proving that anything is possible, that’s exactly what the Tasleem family is doing. It’s hard to argue that anyone is more deserving of a little good fortune in life. With a smile that extends from ear to ear, Wali said, “We are very happy here ... I am very happy.”

No comments:

Post a Comment