Jerry Chabot has been an over-achiever for most of his life. He finished high school when he was 16, started college when he was 17, and went to boot camp later that same year.

Chabot was awarded a promotion in boot camp before his drill instructors found out that he was a reservist. They would’ve rather promoted an active-duty Marine, but he had proved himself through his discipline and work ethic.

Thirty years later, the same set of principles that helped him succeed in the military help Chabot build nearly bomb-proof carbon wheelsets from his shop in Vermont.

“Initially, I didn’t think I’d go in the military at all,” says Chabot.

He’d known for a long time that he wanted to be involved in mechanical engineering. Chabot spent time as a youth tinkering and messing with bikes, cars, and other machinery. But, he had another calling along the way.

“I had a chip on my shoulder and this superiority thing going on,” he says. “I definitely enlisted [in the Marines] because I wanted to prove something that people couldn’t take away from me.”

Outside of the Marine Corps, it might’ve been working, but his platoon didn’t know what to make of Chabot, at least for a little bit. Most recruits hang a picture of their girlfriend on their wall or foot locker. Chabot missed riding his bike the most though, and pinned up a photograph of his Vitus road bike instead.

“It didn’t play super well,” he recalls. But, after the skinsuit insults and maybe a few bruises along the way, he still earned a meritorious promotion to private first class before he graduated.

Back home on the East Coast, he was going to college in Montreal and driving the four hours between there and his reserve station in Manchester, New Hampshire. A little more than halfway through the fall semester of 1990, he got orders to deploy to Kuwait for Desert Storm.

His professors told him that he would lose any credit from that semester and have to retake all of his classes. Back then, then weren’t the same laws and protections for service members in school that there are now.

Chabot’s unit staged in Saudi Arabia on the border of Kuwait. They would prepare, drill, and practice for the push into Kuwait to force the Iraqis out.

He remembers the unusual pace of the Gulf War and the transition from staging to invasion.

“It was super boring, and then it was like super intense for a week.”

The Marines rid Kuwait of Iraqis at a record pace. Chabot says that direct fire between his unit and Saddam’s army was pretty minimal. The Iraqis would fire a few shots at the Marines and surrender quickly thereafter.

Aside from quick battles, the Marines regularly dealt with chemical threats and the unhealthy smoke from oil well fires.

“It was horrendous,” said David Funk. Funk served as Chabot’s platoon sergeant in Desert Storm. “You could count a hundred [fires] in any direction and get tired of counting. It could be the middle of the day and it was as black as any night you’ve ever seen,” he said.

The worst of Chabot’s time in country though, was the result of a friendly-fire incident.

“We saw it coming in, so we knew it was friendly-fire right away,” he said.

Their unit had finally received a few Humvees before the invasion and the Marines were resting in them. Just down the formation from Chabot, two Marines were inside a mobile radar equipped Humvee. An A-6E Intruder jet picked up a signal from the Humvee as it flew over the Marines’ position and fired a missile.

“One of them died,” says Chabot. His voice, which is usually quick and successive slows down. “Corporal Aaron Pack. I got a KIA bracelet when I got back.”

Although Chabot came back in one piece, he noticed a physical change on his first ride back home.

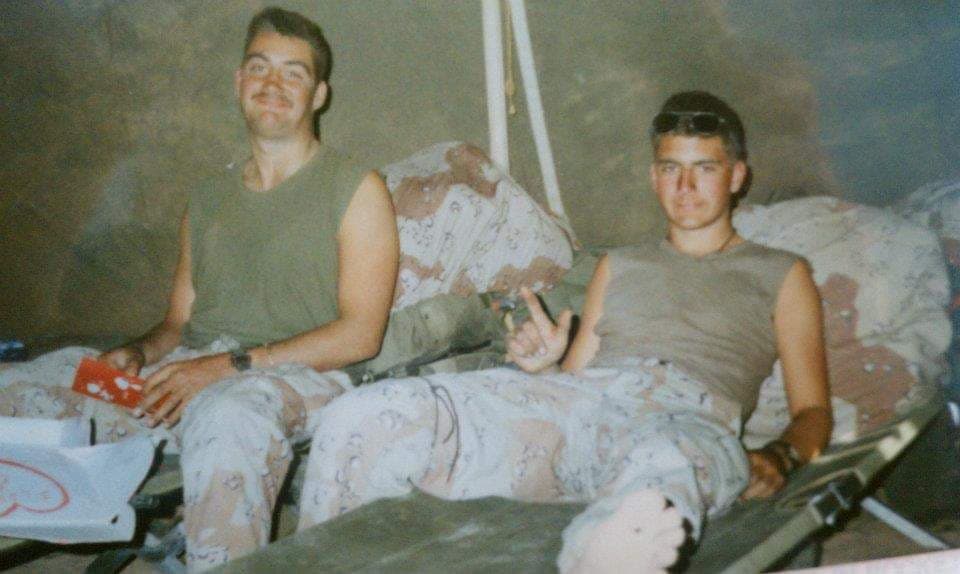

Photo provided by Jerry Chabot.

He rode with a friend across town. Chabot was on his road bike and his friend was on a mountain bike. Chabot could barely keep up and thought something felt off. He and other Marines often only wore bandanas over their faces during the oil well fires.

“I did feel like my lungs were never the same,” he says.

Chabot discharged from the military after a total of eight years service, including active duty and reserve time. He finished engineering school and then decided he wanted to be his own boss. Aside from riding for most of his life and spending time with other athletes, amateur and professional, he didn’t have any actual experience in the bike industry.

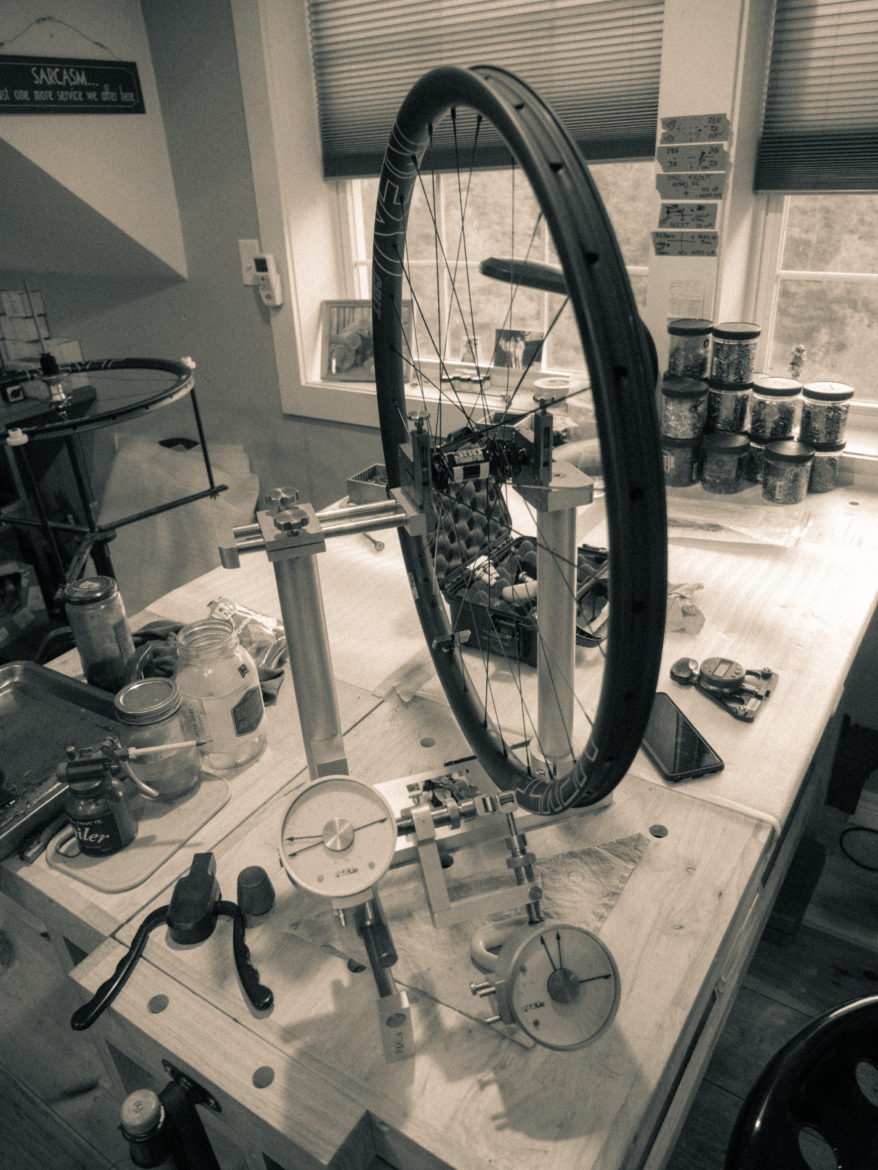

Next Wheels started in 2015 as a riding club at first, after his consulting engineering firm was acquired. It’s grown into a full-time wheel-building business for Chabot. Now he provides consulting engineering services to a manufacturer in China that produces the carbon rims and ships them to Vermont. This is where Chabot’s work really comes into play, and whether that work comes from talent or obsessive discipline is open for interpretation.

“Jerry is precise,” says Noah Tautfest, the owner of Bike Express, a shop in Waterbury, Vermont. “Ever see the guy not looking clean cut?” Tautfest sees Chabot’s own discipline translating directly to the wheel builds.

“You can quantifiably build a good wheel,” says Chabot. He laterally and vertically tensions each spoke in every wheel to levels that are generally tighter than factory-built wheels he has measured. Chabot records the tension and traits of every wheel sold. If a rider experiences a problem or crack in the rim, he can look to his notes, the tensions, or layup on the rim and tweak production on the fly. Large companies can’t do that.

Photo provided by Jerry Chabot. To give carbon wheels an anodized look, Chabot says “just throw money at it.”

“I’m not Enve, or a carbon fiber rim company. [Next] is a wheel-building company.”

While he notes that carbon fiber rim companies like Enve may have more research and development in their rims, Next wheels are meticulously tensioned around the entire wheel, which is said to give it a distinct ride feel.

“I truly believe that you can feel it in my wheels,” he says.

Today, Next sponsors a UCI road bike team, a high school mountain bike team, mountain bike clubs, and a privateer racing the Enduro World Series. The brand lineup includes carbon wheels made for cross country and trail named the Grit, a 27.5+ wheel, and an enduro or all-mountain wheel called the Huck. The Grit and Huck come in both 27.5- and 29-inch sizes. Chabot is hoping to have 200-300 wheelsets built by the end of the year, all by himself and all by hand.

“The Marines instilled in me an ability to suffer,” he says. “Building wheels is hard, manual labor. I love that about it. You can have a lazy day and still push your email around and get [things] done, but [other times] it’s hard and I get tired and have to just suck it up and get the shit done. The Marines gave me that ability.”

No comments:

Post a Comment