For more than a century, the United States Forest Service has employed men and women to monitor vast swaths of wilderness from isolated lookout towers. Armed with little more than a pair of binoculars and a map, these lookouts served as an early warning system for combating wildfires. Eventually the towers would be equipped with radios, and later still a cellular or satellite connection to the Internet, but beyond that the job of fire lookout has changed little since the 1900s.

Like the lighthouse keepers of old, there’s a certain romance surrounding the fire lookouts. Sitting alone in their tower, the majority of their time is spent looking at a horizon they’ve memorized over years or even decades, carefully watching for the slightest whiff of smoke. The isolation has been a prison for some, and a paradise for others. Author Jack Kerouac spent the summer of 1956 in a lookout tower on Desolation Peak in Washington state, an experience which he wrote about in several works including Desolation Angels.

Like the lighthouse keepers of old, there’s a certain romance surrounding the fire lookouts. Sitting alone in their tower, the majority of their time is spent looking at a horizon they’ve memorized over years or even decades, carefully watching for the slightest whiff of smoke. The isolation has been a prison for some, and a paradise for others. Author Jack Kerouac spent the summer of 1956 in a lookout tower on Desolation Peak in Washington state, an experience which he wrote about in several works including Desolation Angels.

But slowly, in a change completely imperceptible to the public, the era of the fire lookouts has been drawing to a close. As technology improves, the idea of perching a human on top of a tall tower for months on end seems increasingly archaic. Many are staunchly opposed to the idea of automation replacing human workers, but in the case of the fire lookouts, it’s difficult to argue against it. Computer vision offers an unwavering eye that can detect even the smallest column of smoke amongst acres of woodland, while drones equipped with GPS can pinpoint its location and make on-site assessments without risk to human life.

At one point, the United States Forest Service operated more than 5,000 permanent fire lookout towers, but today that number has dwindled into the hundreds. As this niche job fades even farther into obscurity, let’s take a look at the fire lookout’s most famous tool, and the modern technology poised to replace it.

THE OSBORNE FIREFINDER

At the most basic level, the job of the fire lookout is to detect and locate the first signs of a possible fire. This boils down to carefully scanning the horizon for signs of smoke, and if seen, plotting the position of the plume on a map and communicating its location to the on-duty fire crews. All a fire lookout actually needs to accomplish this task is a map of the area he or she is monitoring, and ideally a pair of binoculars or a small telescope. Indeed, prior to the 20th century, this would have been the extent of the equipment available.

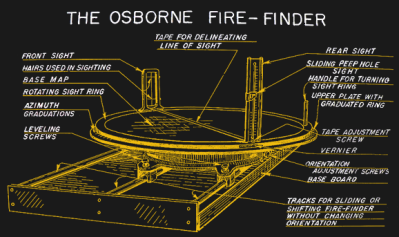

But in 1911, William Bushnell Osborne invented the tool which would ultimately become the hallmark of the fire lookout: the Osborne Firefinder. The device, a type of alidade, featured a large circular map of the surrounding area and a sighting apparatus that rotated above it. Some variations of the Firefinder used what was effectively a rifle scope, but others used a “peep” sight that was nothing more than a strip of metal with a small hole drilled into it. In either case, the operator would rotate the Firefinder until they could see the base of the smoke column through the sights.

But in 1911, William Bushnell Osborne invented the tool which would ultimately become the hallmark of the fire lookout: the Osborne Firefinder. The device, a type of alidade, featured a large circular map of the surrounding area and a sighting apparatus that rotated above it. Some variations of the Firefinder used what was effectively a rifle scope, but others used a “peep” sight that was nothing more than a strip of metal with a small hole drilled into it. In either case, the operator would rotate the Firefinder until they could see the base of the smoke column through the sights.

The center of the circular map represented the location of the tower, with compass headings marked around the entire circumference. When the smoke was sighted in, the degrees of rotation marked by the Firefinder would correspond to the azimuth of the target. This heading could be forwarded to other nearby towers and, assuming they could see the smoke from their vantage point, allowed for triangulation of the fire’s location.

If there were no other towers in the area, or they were unable to see the smoke from their position, the operator of the Firefinder could employ the elevation measurement marks on the sights to estimate distance. With the compass heading and an idea of how distant the smoke was from the base of the tower, crews on the ground would at least have enough information to start their search.

BACK TO THE FUTURE

The Osborne Firefinder was a simple device with few moving parts, and yet when properly set up and calibrated, allowed fire lookouts to locate potential danger with unparalleled accuracy for the era. Realistically, the United States Forest Service didn’t have a better way of pinpointing the location of a fire until the use of aircraft became practical. But even still, the Firefinder was a compelling option as it was cheap and easy to use.

Moreover, the Firefinder went through its own evolution over the years, with new variations steadily increasing its accuracy and utility. These incremental updates culminated with the 1934 version, of which more than 3,000 were manufactured and distributed to lookout towers both domestically and abroad. Incredibly, this version was still being manufactured in the United States up until 1989.

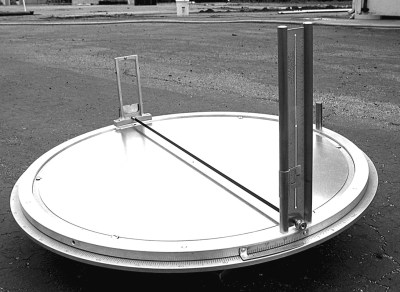

But by the 2000s, there was a problem. With original Osborne Firefinders still in use all over the country, and the supply of spare parts dwindling, the Forest Service’s San Dimas Technology and Development Center (SDTDC) decided to investigate replicating the vintage devices. The various models of the Firefinder were compared, disassembled, and modeled in AutoCAD. Some slight modifications were made based on input from veteran fire lookouts, and prototypes of the new and improved 2003 model Firefinder were built and tested at the Odell Butte and Green Mountain lookout towers in Oregon.

After the successful test program, Palmquist Tooling in California began manufacturing new Firefinders and replacement parts that were largely backwards compatible with the original models. Upgrades for the modern Firefinders included replacing cast iron components with aluminum to save weight, and the addition of nylon bearings to reduce wear.

EYES IN THE SKY

Firefinders, whether original Osborne or the updated SDTDC versions, are still actively being used today. Given the fixed location of the tower as a reference point, they give lookouts a simple and reliable way to determine with reasonable accuracy the coordinates of a potential fire. But the reality is that automated systems can do the same job faster and with a much higher degree of accuracy than any human.

Currently, there are a number of different high-tech approaches being used or considered for fire detection. A new space-based system was just brought online over the summer that uses data from several orbiting spacecraft, including the latest GOES weather satellites, to provide continuous monitoring of potential or ongoing wildfires. With updates being pushed out as quickly as once per minute, the system gives emergency agencies a high-level view of the situation in nearly real-time, allowing for efforts to be coordinated far more efficiently than was possible in the past.

But there’s only so much that can be seen from space. To provide a closer view of conditions on the ground without endangering human life, several small Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) have been approved for use in and around active wildfires for the purposes of on-site monitoring. These craft can get far closer to the fire than manned vehicles or firefighters can, and provide crucial information on how best to combat it. Similar UAVs proved invaluable during the blaze at Notre Dame cathedral, and represent something of a revolution in close-quarters firefighting technology.

FREAKS ON THE PEAKS

It’s undeniable that technology has largely supplanted the fire lookouts at this point. The US Forest Service actually rents out many of the towers as summer vacation cabins now, as the task they were built for has been antiquated by satellites and UAVs. But in the parts of the country where the towers are still staffed with self-identified “Freaks on the Peaks”, the old ways are alive and well.

Even with all the modern technology available, human lookouts can still be a viable option. For one, they’re cheap: most fire lookouts are employed only during the summer months and paid an average of $12 USD per hour. Some of the lookouts have been stationed at the same tower for decades, which gives them invaluable experience with the nuances of the land that can be critical in a crisis. Operating conditions also need to be taken into consideration: UAVs have a difficult time flying in the summer thunderstorms which have been known to trigger wildfires.

Even with all the modern technology available, human lookouts can still be a viable option. For one, they’re cheap: most fire lookouts are employed only during the summer months and paid an average of $12 USD per hour. Some of the lookouts have been stationed at the same tower for decades, which gives them invaluable experience with the nuances of the land that can be critical in a crisis. Operating conditions also need to be taken into consideration: UAVs have a difficult time flying in the summer thunderstorms which have been known to trigger wildfires.

With time, even these advantages are likely to be overcome by newer and more advanced automated systems. But until then, a small army of men and women will still climb their towers every spring and keep vigil over the forest with little to keep them company beyond an Osborne Firefinder that was likely built decades before they were born.

No comments:

Post a Comment