Many thanks to Mark Hirst, who shares the following guest post:

Many thanks to Mark Hirst, who shares the following guest post:

Pick and Pluck Foam

The old adage of ‘measure twice and cut once’ is very apt when using pick and pluck foam. The inserts are not cheap and mistakes are hard to rectify.

Whether you are preparing a large case with several items in a shared insert, or focussing around a single item, planning the layout is key.

Item weight is also a factor to consider, as this will affect decisions on wall thickness between items and the case.

Finally, how hostile is the environment likely to be? Is the case going in your backpack or car where you’re in careful control, or is going to be subject to careless handling by others?

Planning the layout

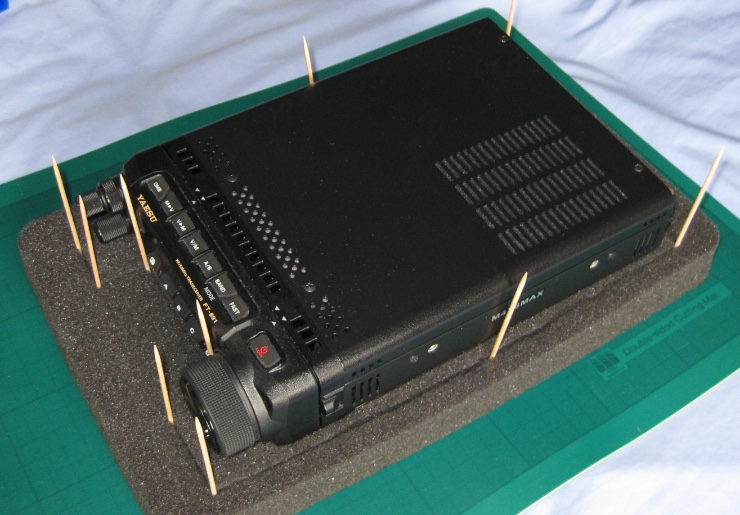

Once you’ve settled on a case size and how much padding you need, a non-destructive way of planning the layout is to use cocktail sticks.

These can be inserted into the corners of the foam segments to trace the outline of the radio and any items such as controls and ports that may extend from the body.

Since the size of the segments is in fixed increments, matching the exact dimensions of the radio is down to pure luck. I would go for a slight squeeze on the radio body if feasible to make sure it’s always in contact with the foam, but give some breathing room around the controls and ports.

The example below is a case I use for backpack transport. It has rather thin but adequate side walls for that purpose. I prioritised wall thickness facing the front and back of the radio, and also on the side opposite the carry handle. Note how the foam comes right up against the body of the radio, but leaves the front controls with some clearance.

This has the benefit of keeping any sudden shocks away from the controls, and also reduces the number of places where foam is subject to tearing and compression when the radio is inserted and removed.

Separating the foam

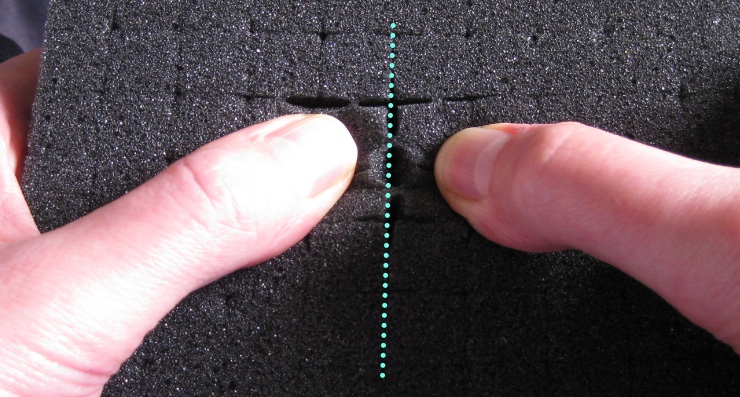

The best place to start is along the planned route of a long side wall. Use your thumbs to separate the surface of two segments on one side from two segments on the other.

Once the surface tear has got going, you should be able push a finger down between the four segments, extending the tear till it reaches the bottom of the foam. At this point, you have a cut all the way through.

Now you can peel the foam apart at the upper surface in each direction, using your forefinger to again push down between the segments to complete the separation down to the lower surface.

Work carefully around the cutouts and protrusions accommodating the controls. The protrusions are potential weak points at this stage, so be sure to proceed slowly.

If you need to practice, you can always start by separating segments deep within the section that will be removed till you get the hang of it.

Reinforcement

While pick and pluck means you don’t need special tools or templates to cut the foam, the remaining material in your insert is inherently weaker than a solid structure.

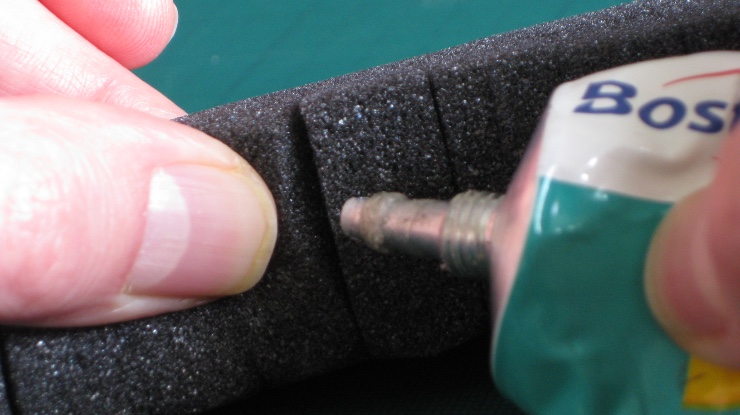

The solution I’ve used is to fill the residual cuts with a solvent free adhesive. Solvent free adhesives are often aimed at children for safety reasons, and while there are solvent based adhesives for foam, the one I used dries clear with a resilient flexible bond that is stronger than the foam itself.

I run a finger gently along the exposed walls, edges, and around the protrusions. This makes the potential weak points and stress areas immediately apparent as segments naturally separate along the pick and pluck cuts.

Armed with a tube of adhesive and a finger (usually a thumb), you can gently open the weak point and then run the nozzle of the tube down the cut, dispensing generous amounts of adhesive as you go. The two sections of foam close up as the nozzle passes by, with the adhesive soaking into both sides. As long as you don’t go overboard, the adhesive will stay within the join and you won’t have to wipe away any excess.

Side walls are not subject to the same stress as protrusions, but you will probably still spot sections with deeper cuts that need attention, and you will definitely want to reinforce the corners.

I’ve allowed at least a day to be sure the adhesive has set. It’s worth going over the insert again to see if you missed anything the first time round.

The Adhesive

The Bostik solvent free adhesive resembles runny white toothpaste when dispensed from the tube, but dries clear when set.

Inevitably, when I tried to find more of it recently, I discovered that the easily recognisable colour and branding had made way to a confusingly generic scheme shared across a variety of different adhesive types from the manufacturer.

I found this old listing for Bostik 80518 on Amazon UK, and another here on Amazon US. Based on the product number, a modern equivalent seems to be here.

I’m sure there’s nothing unique about this particular product, other than I’ve found it to be foam friendly over the years. Aside from being solvent free, its ability to seep into the foam is a key asset.

Since the first step of creating an insert leaves you with a potentially discardable piece of foam anyway, you have plenty of raw material to experiment with if in doubt.

Additional Reinforcement

Even if you have been generous with the side walls of your foam insert, a heavy radio might demand some additional work to ensure the longevity of the foam.

While the example case shown above worked OK to start with, I noticed that the floor of the case and the side wall facing the back of the radio were taking a beating.

The problem was caused by the feet of the radio, cooling fins, power and antenna connectors. During transport, these were pushing into the foam with the full weight of the radio behind them. Subject to such concentrated point forces, I could see that the foam wasn’t going to last.

Using very thin and very cheap flexible plastic cutting boards from my local food market, I cut out panels which spread the point compression across a much wider area.

Now when I put the case into a backpack, I ensure that the radio is sitting on its tail with the cooling fins against the rear panel.

Conclusion

While it’s possible to create ad-hoc transport solutions for radios, there’s nothing quite as satisfying as a sturdy padded case that is made to measure. The cases are forever, but the foam needs care and attention, so I hope these tips help you build a lasting solution for safely transporting your pride and joy.

Oh wow! Thank you so much for this timely post and for helping me as I kit-out a Pelican case for my Icom IC-705.

Readers, click here to check out Mark’s previous post about the case he uses for his Yaesu FT-891.

Thanks again for sharing your best practices, Mark!

No comments:

Post a Comment