About one week ago, I shared some fascinating data from the Tax Foundation about how different nations penalize saving and investment, with Canada being the worst and Lithuania being the best.

I started that column by noting that there are three important principles for sensible tax policy.

- Low marginal tax rates on productive behavior

- No tax bias against capital (i.e., saving and investment)

- No tax preferences that distort the economy

Today, we’re going to focus on #1, specifically the tax burden on the average worker.

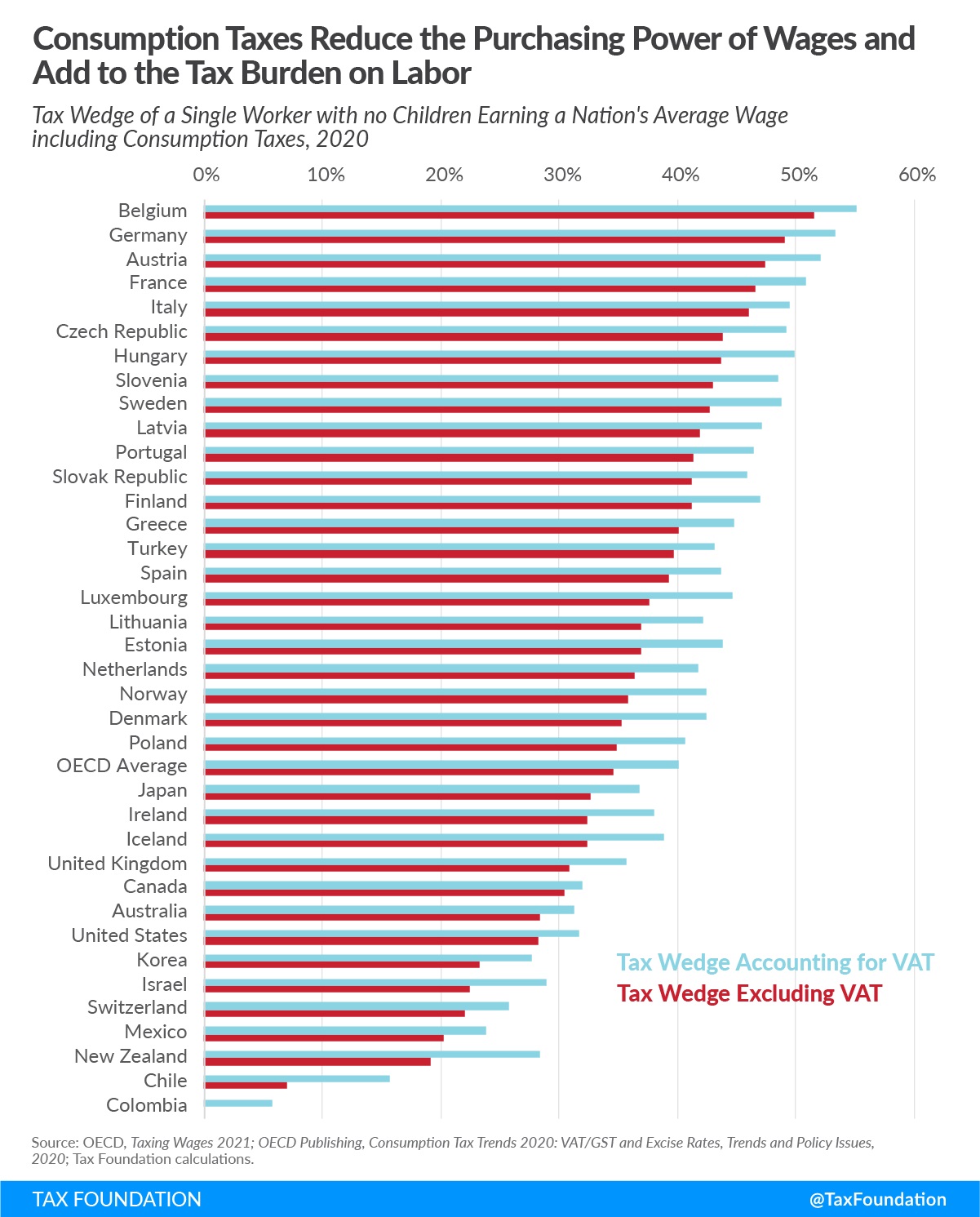

And, once again, we’ll be citing some of the Tax Foundation’s solid research. Here are their numbers showing the tax burden on the average worker in OECD nations. As you can see, Belgium is the worst place to be, followed by Germany, Austria, and France.

Colombia has the lowest tax burden on average workers, though that’s mostly a reflection of low earnings in that relatively poor nation.

Among advanced nations, Switzerland has the lowest tax burden when value-added taxes are part of the equation, while New Zealand is the best when looking just at income taxes and payroll taxes.

Here’s some of what the Tax Foundation wrote in its report, which was authored by Cristina Enache.

Average wage earners in the OECD have their take-home pay lowered by two major taxes: individual income and payroll (both employee and employer side). …The average tax burden among OECD countries varies substantially. In 2020, a worker in Belgium faced a tax burden seven times higher than that of a Chilean worker.

…Accounting for VAT and sales tax, the average tax burden on labor in 2020 was 40.1 percent, 5.5 percentage points higher than when only income and payroll taxes are considered. …The tax burden on labor is referred to as a “tax wedge,” which simply refers to the difference between an employer’s cost of an employee and the employee’s net disposable income. …Tax wedges are particularly high in European countries—the 23 countries with the highest tax burden in the OECD are all European. …Chile and Mexico are the only countries that do not provide any tax relief for families with children but they keep the average tax wedge low.

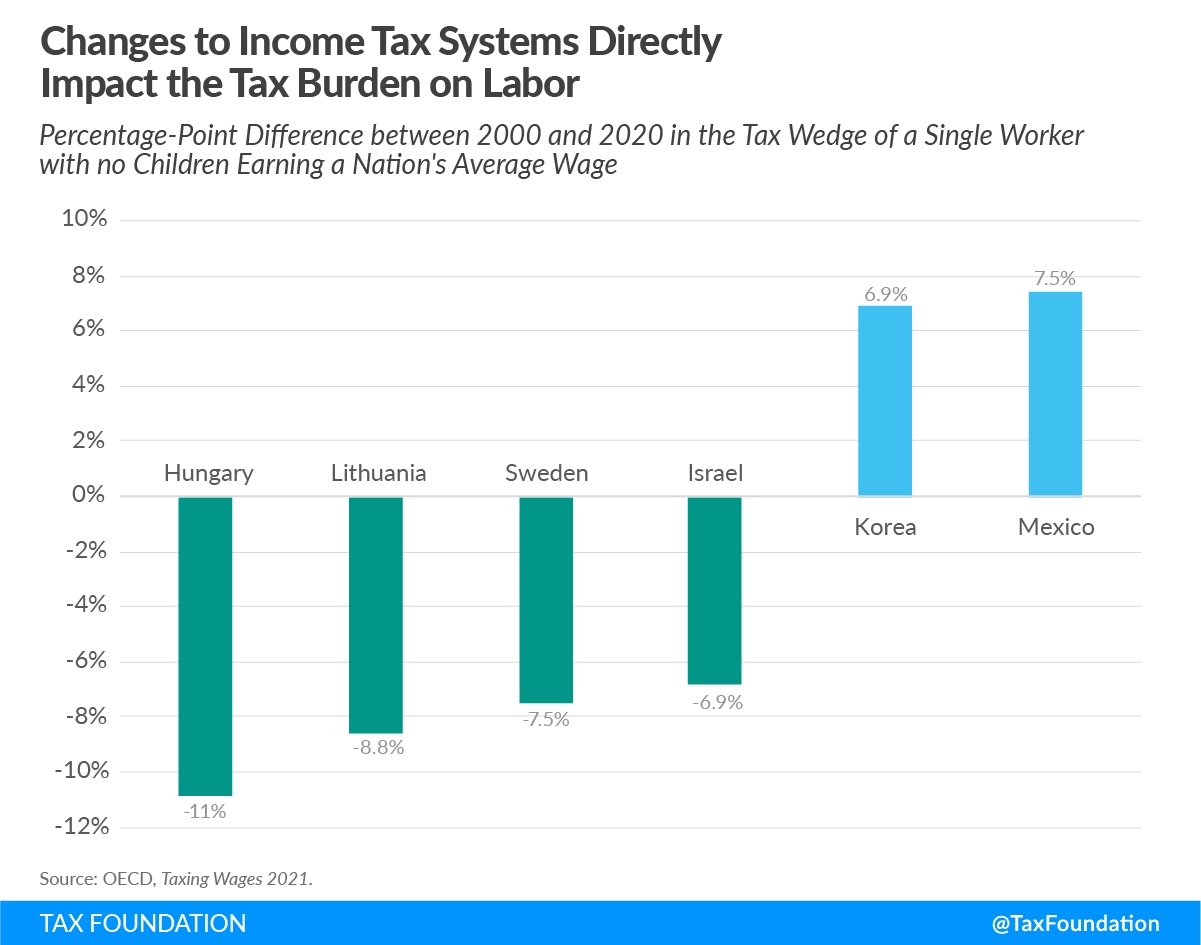

Here’s a look at which countries in the past two decades that have made the biggest moves in the right direction and wrong direction. Kudos to Hungary and Lithuania.

And you can also see why I’m not overly optimistic about the long-run outlook for Mexico and South Korea.

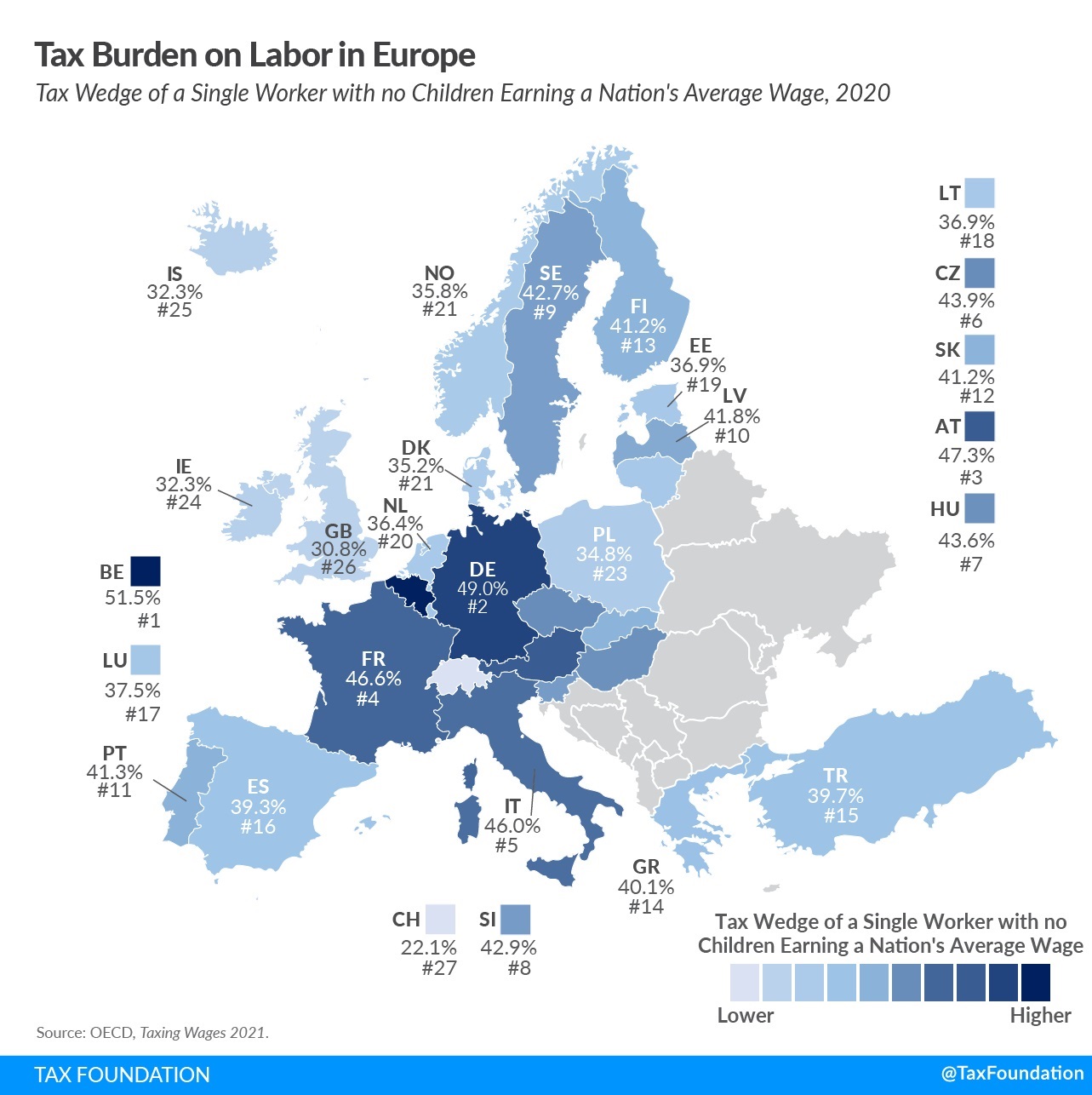

The report also has a map focusing on tax burdens in Europe. The darker the nation, the more onerous the tax (notice how Switzerland is a light-colored oasis surrounded by dark-colored tax hells).

The report also notes that average tax wedges only tell part of the story. If you want to understand a tax system’s impact on incentives for productive behavior, it’s important to look at marginal tax rates.

The average tax wedge is…the combined share of labor and payroll taxes relative to gross labor income, or the tax burden. The marginal tax wedge, on the other hand, is the share of labor and payroll taxes applicable to the next dollar earned and can impact individuals’ decisions to work more hours or take a second job. The marginal tax wedge is generally higher than the average tax wedge due to the progressivity of taxes on labor across countries—as workers earn more, they face a higher tax wedge on their marginal dollar of earnings. …a drastic increase in the marginal tax wedge…might deter workers from pursuing additional income and working extra hours.

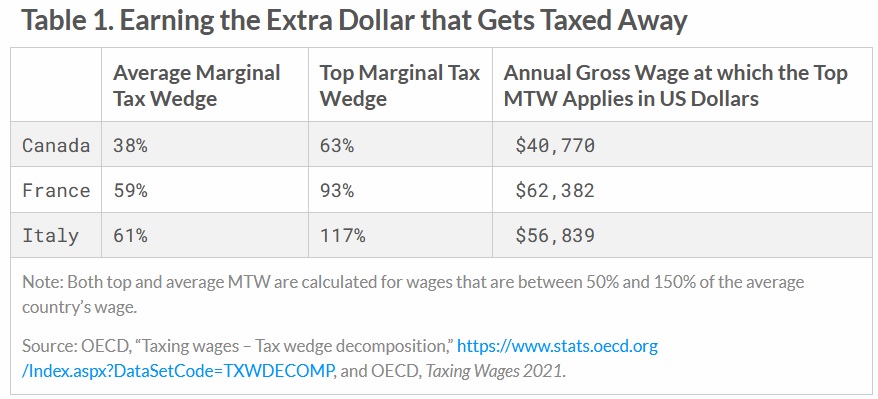

And here’s Table 1 from the report, which shows that marginal tax rates can be very high, even at relatively modest levels of income.

In what could be a world record for understatement, this data led Ms. Enache to conclude that Italy’s tax system “might” deter workers.

In 2020 an Italian worker making €38,396 (US $56,839) faced a marginal tax wedge as high as 117 percent on a 1 percent increase in earnings. Such marginal tax wedges might deter workers from pursuing additional income and working extra hours.

Though that’s not the most absurd example of over-taxation. Let’s not forget that thousands of French taxpayers have had tax bills that were greater than their entire income.

Sort of like an Obama-style flat tax, but in real life rather than a joke.

P.S. As I’ve previously noted, Belgium is an example of why a country can’t simultaneously have a big government and a good tax system.

No comments:

Post a Comment