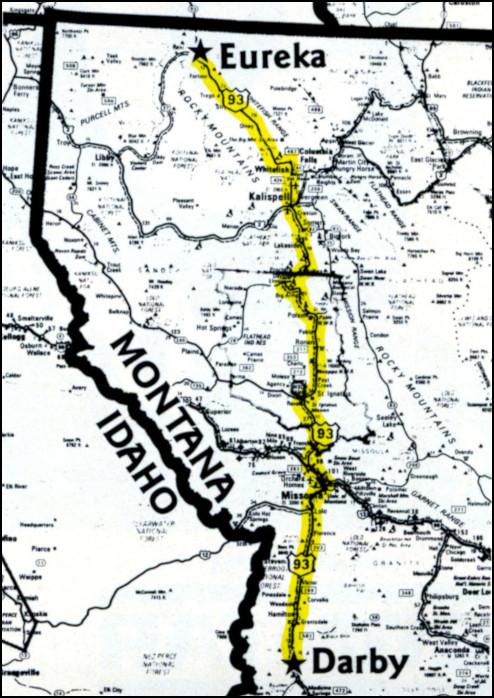

On May 13, 1988, a convoy of trucks more than 12 miles long rolled down U.S. Highway 93 in Montana. Onlookers gawked and cheered as over 300 trucks fully loaded down with logs passed by one by one. This impressive display was actually a unique form of protest by the local logging community. Frustrated by an increase in the amount of protected wilderness, court rulings that hampered timber harvesting, cancelled timber sales, and the closing of mills, the local logging industry was now fighting back. The event would become known as the Great Northwest Log Haul.

The Great Northwest Log Haul rolls out from Eureka, Montana, on the morning of May 13, 1988. Note the police escort at the front of the line. (Image ID# AFA521)

In the July 1988 issue of Timber Harvesting, Keith Olson, Executive Director of the Montana Logging Association at the time, described what led up to the Log Haul:

It all started so simply. It was Tuesday evening, the 26th of April. In Eureka, 1,000 citizens gathered—there are only 1,100 in the town—to form the North Lincoln County Coalition. Citizens of Eureka, and other northwest Montana communities, were upset about a federal appeals court decision that blocked 130 to 150MMBF of timber sales planned in the nearby Yaak River Valley.

A comment was made that if local timber-dependent communities weren’t careful, Eureka might suffer the same fate as Darby, a community 250 miles south that had a sawmill recently close because of a lack of logs.

Sometime during the evening, Mike Mrgich, a local log hauler, wondered aloud if Eureka should consider hauling a few loads of logs to Darby. After all, that’s what farmers did with hay when drought-stricken counterparts were short of feed a couple of years ago. The concept began to grow on the community. At their first formal planning session supporters thought they might be able to put together a convoy of 40 loads.

Meanwhile, in Libby, that community geared up for a rally. On Wednesday, the 4th of May, U.S. Senators Max Baucus and John Melcher would arrive to discuss with concerned citizen from across Montana such issues as timber sale appeals, wilderness legislation, preservationist litigation, endangered species, etc…

When Baucus and Melcher arrived they were received by a crowd of more than 3,000 involved in Montana’s timber industry, people from northern Idaho and western Montana. Concern was mounting. Interest was growing. An industry which historically invested millions of dollars in machinery and equipment—but seldom invested a nickel in community awareness was beginning to realize the future of timber-dependent communities was legitimately threatened.

The senators spoke to the crowd and tried to calm its fears, albeit unsuccessfully. Baucus had provoked the industry’s wrath by suggesting to the press that he sensed a shift in public attitude that favored more wilderness. Bruce Vincent, logger and convoy organizer of Libby, suggested that [Baucus] should ask those present how they felt. The result: no more wilderness, 3,000±; more wilderness, 0.

In the days that followed the Libby rally, the concept of hauling logs from Eureka to Darby literally exploded. Communities from throughout western Montana and northern Idaho volunteered their participation and soon the Great Northwest Log Haul was a full blown reality… and a media sensation.

National television and other media indeed showed up on the morning of May 13th as the Great Northwest Log Haul was set to begin. Loggers from around the state, as well as some from Washington, Idaho, and elsewhere, converged into the small town of Eureka, Montana, less than nine miles from the Canadian border.

At 8am the gathered trucks began to roll south. The destination was Darby, a town 250 miles south, where a mill operated by Darby Lumber, Inc. had recently closed because of lack of logs to saw. The convoy of log trucks was both a showcase of strength and a last-ditch effort to save the mill.

Trucks driving south on highway 93 through Montana. (Image ID# AFA520)

As the convoy slowly made its way along U.S. Highway 93, more trucks joined up. Eventually stretching up to fifteen miles long, the line of log trucks was an incredible sight. Passing through Missoula that afternoon, crowds cheered as even more trucks joined in.

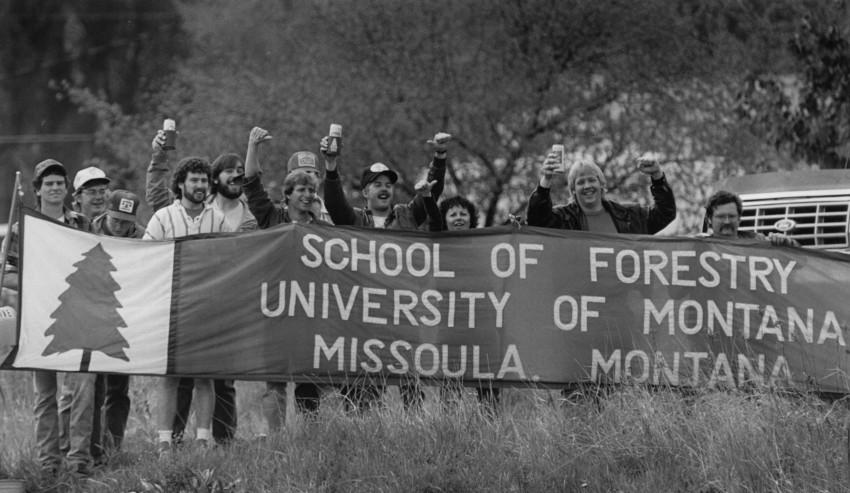

A group from the University of Montana cheers as the Log Haul passes through Missoula. (Image ID# AFA522)

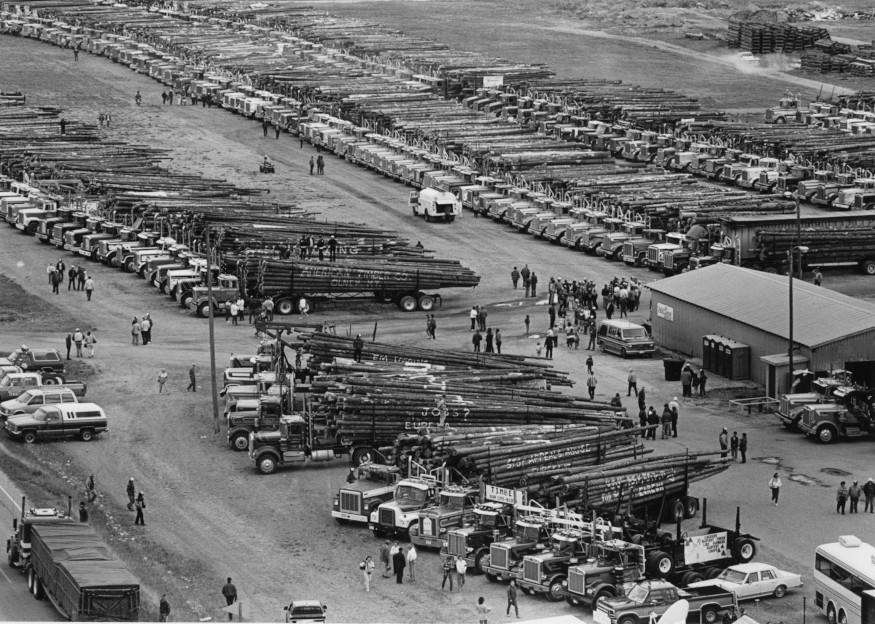

At 4pm the first trucks pulled into the yard at Darby Lumber. For over an hour the trucks would keep arriving one by one—more than 300 of them in all—ultimately bringing around one million board feet of logs to the closed mill. Darby Lumber owner Bob Russell called the event “historical” and “the biggest thing that’s ever happened like this.” Russell paid a greatly reduced cost for the logs, while the truckers donated their hauling expenses and local communities pitched in to cover some fuel costs.

The Darby mill was now guaranteed several weeks of operations. But more importantly, the area’s loggers had shown their collective strength to a national audience. The Log Haul served as not just a jolt to the mill in Darby, but also a shot in the arm to the entire logging industry. A new sense of camaraderie emerged as the logging community saw the strength and success of their cooperative effort.

Over 300 trucks arrived at the Darby Lumber mill at the end of the Log Haul. (Image ID# AFA523)

Keith Olson of the Montana Logging Association summed up the event as follows:

From Missoula to Darby, The Great Northwest Log Haul stole your breath, left goose bumps on your body, welled your tears, tugged at your emotions and lit your face with pride…

It took communities to pull off the Great Northwest Log Haul. It will take communities to keep the momentum going in the timbered Northwest. It is no coincidence that every community ends in the word “unity.” Today, we are an indus-tree with renewed pride! As the convoy becomes a proud memory, we must remember that timber community pride is as renewable as is the timber resource harvest.

While the protest had an immediate impact, it was ultimately short-lived. The following year the mill closed, and timber sales and harvesting levels declined throughout the region over the next several years. Since then, the town of Darby—situated on the highway between Glacier and Yellowstone national parks—has seen its economy slowly turn its focus from timber to tourism.

Drivers gathering in Darby at the conclusion of the Log Haul. (Image ID# AFA524)

The sight of 300 log trucks passing through Montana was an image long remembered. (Image ID# AFA520)

No comments:

Post a Comment