Norman Rockwell’s 1942 painting Freedom of Speech was a huge success.

Norman Rockwell’s 1942 painting Freedom of Speech was a huge success.

(This was one of four paintings he did to illustrate President Franklin Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms. See Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms and Rockwell’s Four Freedoms.)

Rockwell himself liked it the best of his Four Freedoms paintings, and it was popular with the public:

Norman Rockwell’s Freedom of Speech is among the most famous works of American art, arguably as well known as James McNeill Whistler’s portrait of his mother and Emanuel Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware.

(source, p. 55)

Freedom of Speech was the only one of Rockwell’s Four Freedoms paintings that was based on an actual event. This post is the story of the event and the painting.

In the 1940s Norman Rockwell lived in the small town of Arlington, Vermont. On November 9, 1940 the Arlington school burned. A committee led by Arlington resident John Fisher, husband of the noted author Dorothy Canfield Fisher, proposed building a new school that would cost more than the insurance settlement, and would require the town to borrow money. A special town meeting was held on January 18, 1941 to consider the matter.

Town meetings are a New England tradition, and especially in Vermont. Meetings of the citizens in the town are required to approve municipal borrowings and budgets. Citizens act as the legislative branch of government during town meeting.

Norman Rockwell attended that Arlington town meeting in January 1941. Most citizens present were in favor of John Fisher’s proposal. But Rockwell’s neighbor, a farmer named Jim Edgerton, rose to speak against the proposal. Times were hard on the farm, and he did not want to pay more taxes. He thought that Arlington students could be tuitioned out to neighboring towns. Everyone listened respectfully to what he had to say, and then proceeded to vote 119 to 15 in favor of building a new school as proposed and 114 to 18 in favor of borrowing the money needed to do so.

Events did not turn out all bad for Mr. Edgerton:

On an ironic note, when ground was broken for the new school a few weeks later, Edgerton became part of the construction crew. He earned seventy-five cents per hour for an eight-hour day. Later, as head carpenter, he made ninety cents an hour. As it turned out, the school he had so famously opposed would eventually help to salvage his family’s finances.

(source, p. 59)

On another ironic note, that town meeting in January 1941 was less than two weeks after President Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms speech. Rockwell had been inspired by that speech and he spent considerable time in 1941 thinking – without success – about how to illustrate the Four Freedoms. One night in early 1942 he awoke at 3 AM with a flash of inspiration: he could use Jim Edgerton’s speech of a year earlier, and the respectful attention of his neighbors, to illustrate the concept of freedom of speech. In a Vermont town meeting, every citizen has the right to speak and be heard, even for an unpopular position.

Rockwell spent substantial time in 1942 designing the scene he wanted to show in the painting. He chose another neighbor, the Lincolnesque Carl Hess, as the model for the speaker. Hess owned and operated a gas station and car repair shop in Arlington. The speaker, with a town report in his pocket, is without a tie and clearly works with his hands. The audience includes men wearing ties who likely do not work with their hands. The calm speaker dominates the painting, but the scene also includes many respectful eyes and ears. The corner of the blackboard points to Norman Rockwell himself.

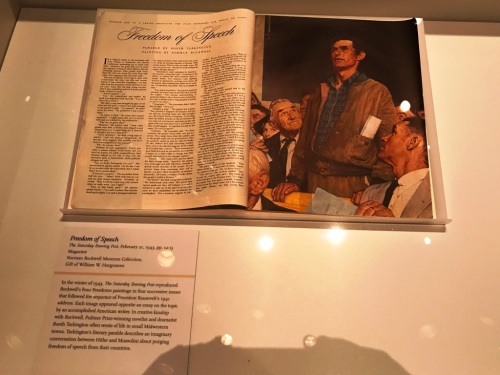

Freedom of Speech was printed in the Saturday Evening Post on February 20, 1943. It was not on the cover, as were many Rockwell illustrations both before and after, but inside the magazine and paired with an essay by Pulitzer Prize winner Booth Tarkington:

Tarkington’s essay was an imaginary parable about a young Adolf Hitler and a young Benito Mussolini meeting by chance at an inn in the Alps and conspiring to eliminate freedom of speech in their countries.

Tarkington’s essay was an imaginary parable about a young Adolf Hitler and a young Benito Mussolini meeting by chance at an inn in the Alps and conspiring to eliminate freedom of speech in their countries.

Rockwell’s paintings of the Four Freedoms in the Saturday Evening Post were a huge success. The Post received more than 60,000 favorable letters. One woman from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, wrote of Freedom of Speech that “every town hall in the land should have one on its walls.” (source, p. 45)

This is one of four posts about the Four Freedoms:

1. Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms

2. Rockwell’s Four Freedoms

3. Freedom of Speech Painting (this post)

4. Legacy of the Four Freedoms

Several earlier posts on this blog have discussed Vermont town meetings; see posts with the tag “town meeting.”

Photo credits: I took the photos above at a special exhibit titled “Enduring Ideals: Rockwell, Roosevelt & the Four Freedoms” at The Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan. See the post Legacy of the Four Freedoms for more discussion about this exhibit. Photos taken October 18-19, 2018.

No comments:

Post a Comment